Much of what Muslims believe is unique to the faith—such as Mohammed being the seal of prophets or besieged believers falling asleep for centuries in a cave—are ideas taken from other religious traditions. For example, centuries before the birth of Mohammed, the Iranian prophet Mani (d. 277 CE), founder of Manichaeism, synthesized elements of Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and even Buddhism to produce his own book of recitation/songs, “Psalms of Bema,” secluded himself in a cave and emerged with a “Book of Painting,” claiming to be the promised “Paraclete” in Christianity, a sort of seal of prophets.

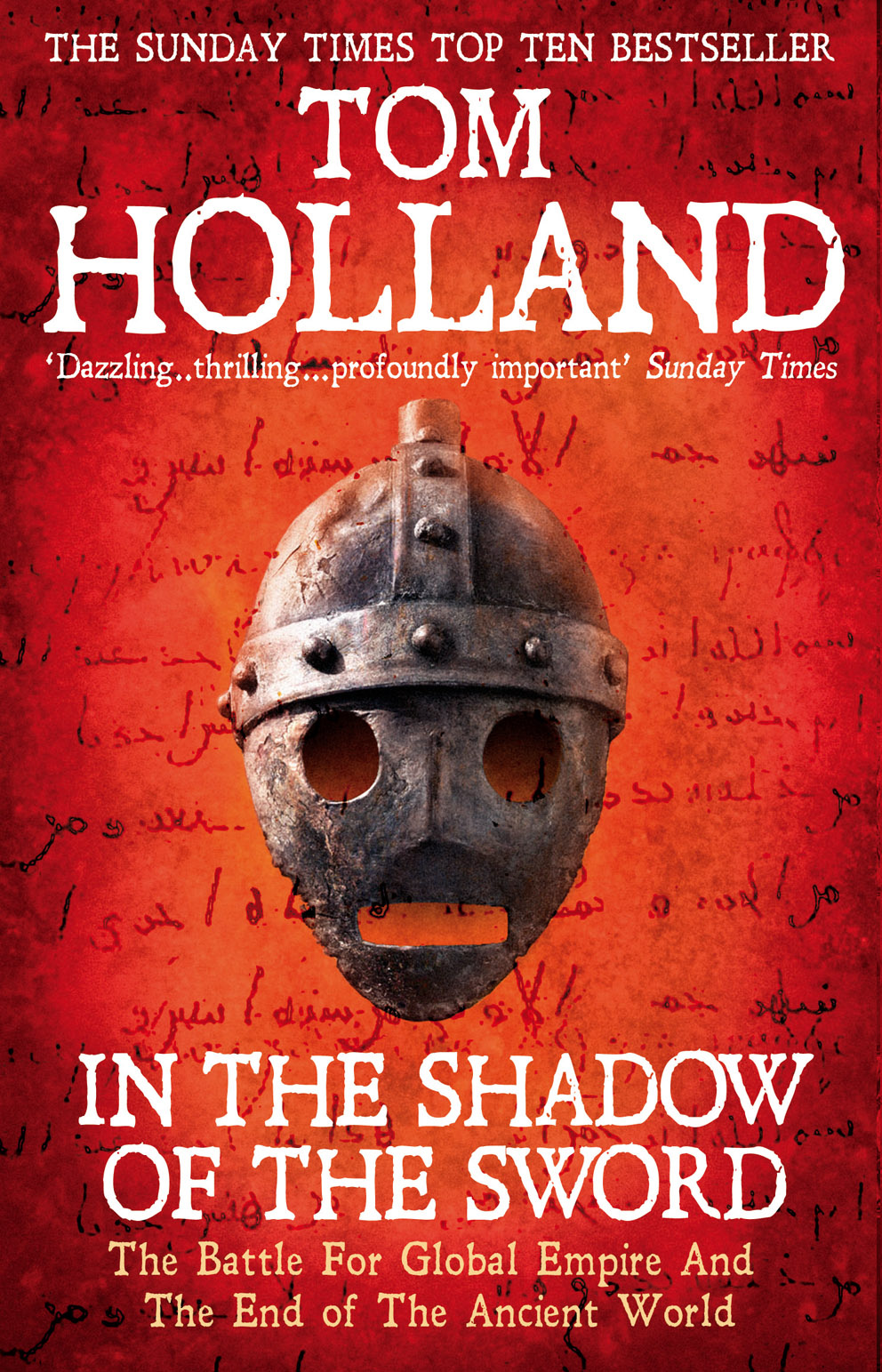

The story of the “People of the Cave” is an older Roman Christian parable from the third century. The Seven Sleepers hide in a cave, near Ephesus in Turkey, to protect their faith during the persecutions of the Roman emperor Decius and end up sleeping for two centuries, awakening during the reign of Theodosius II and dying soon thereafter. Zoroastrian influences, Tom Holland shows in his book In the Shadow of the Sword (2012) shaped the new religion in surprising ways, too. They were the ones who introduced the execution of apostates, the five prayers and the use of the siwak, or toothbrush. (The Koran had assigned apostates to hell, required only three prayers, and made no mention of the siwak.)

Holland notes that the jizya (combining taxation with humiliation) is an old Roman practice, while the reference to Christians as nasara—perhaps the long vanished heretical sect of the Nazoreans, who believed that the Holy Spirit was Christ’s mother—has nothing to do with the prevailing orthodox church. Neither the church nor Jesus would have recognized themselves in the Koran. Maybe the nasara describes the even more ancient adherents of the Gospel of Basilides, who insisted that Christ was not killed or crucified but only appeared to be so. “The echoes of long-muted Christian heretics—of Gnostics and Nazoreans—are sufficiently loud in the [Koran],” comments Holland, “to make one wonder from where, if not from God, they might possibly have come.” Jewish influences are there aplenty, too. “The People of the Trench,” which perplexed interpreters for so long, could very well have been influenced by Jewish thought. The Dead Sea Scrolls refers to hell as “the Trench,” where the damned are consigned to fires. And images of paradise, with its lush pagan scenarios, may well hark back to ancient Greece and Rome. It’s just hard to imagine that such a text was revealed whole in Mecca.

By the dawn of the 7th century, monotheism was the main religion in most of the area, although paganism held its own in a few scattered places, especially in out-of-the-way deserts of Arabia—the ka’ba that Muslims circumambulate during the Hajj pilgrimage is a relic of the pagan reverence for cubes. Such places harbored all manner of heresies and religions.

There is no mention of the word goddess in the Koran, Holland further tells us, nor are pagan shrines or sanctuaries mentioned by name. There is no mention of idols and no archeological record, either. The detailed mention of livestock practices or of produce and vines certainly do not suggest the barren lands of Mecca. Neither does Islam’s obsession with trade. Therefore, it is not clear that pilgrimage to the “House” in Bekka, a “duty owed to God,” is actually in Mecca. Could it have been in in Persia? Was it a reference to the maqom in Mamre (oak tree and well where Abraham rested)? The Quraysh, whose wealthy members owned houses in Syria, could not have been from Mecca, since this kind home ownership was practically unknown in Roman annals. Maybe their name was a corruption of Caesar (qaysar), or shirkat (partnership), which, in Syriac, is qarisha.

The geography of the Koran doesn’t make much sense if we take the traditional accounts of its revelation literally. Moreover, as the scholar F. E. Peters reminds us in The Voice, the Word, the Books (2007), the Koran could not have been written during Mohammed’s time because we have no traces of literacy in 7th-century Mecca and Medina and there were no known tablets in Arabia. Poetry was a public performance and was transmitted orally; like the Koran, it was written down in the 9th to 10th-centuries. When that happened, it was the Arabic of northern Arabia, near Syria, that was used.

As noted in previous articles, the Koran’s literary structure strongly suggests an evolving, ad hoc process of composition. It is a collection of utterances attributed to Mohammed and, according to conventional accounts, arranged into a book in 650 by the caliph Uthman. The inconsistencies that remained in the text were attributed to the Prophet’s forgetfulness and that perennial scapegoat, Satan. And if this weren’t enough, God simply allows himself to abrogate meaning without canceling texts. There is nothing that cannot be fixed by the will of Allah.

Mohammed’s mission (22 years) may have been long compared to those of Jesus and Moses, but he only gets four mentions in the Koran. Sometimes, it seems as if he were the one who is speaking (such as in the sura of al-Fatiha); at most other times, it is either God speaking to humans through him, or God addressing Mohammed directly. In a way, the standard biographies of Mohammed, the siras, were designed to make sense of this complex text.

By the time Caliph Uthman tried to gather the Koranic texts into a book, there was still no “diacritical apparatus” (later borrowed from Syrian Christians) to help confer a more stable meaning on the document. It’s almost certain, F. E. Peters notes, that the Koran, in its current form, was far from being standardized at this point. Koranic inscriptions, dating to 690, found in the Dome of the Rock, as well as the Koranic manuscripts found in Sana` in Yemen, do not always match what’s in the “standard” text we have. This explains why the debate over the proper reading of the Koran, (qira’at) was still alive in the 10th century. The text remained in flux, however, until the Egyptian King Fuad’s commission settled on the “Hafs, from Asim” variation in the printed edition of 1923 or 1924.

Once written down, the mushaf turned into a sacred object, the terrestrial copy of a tablet preserved in heaven. Only those who are purified were allowed to touch it. In fact, a whole literature on purity (tahara) was developed to treat the scared text and other religious matters. Rules were devised on when to touch the Koran, what causes impurity and cancels rituals (such as prayer and pilgrimage), as Islam built its sacred edifice. A few others religions were duly noted, as the Koran recognizes all prophets before Mohammed—some 360,000, in one estimate. But because the tawrat (Torah) and the injil (Gospel) were tampered with (tahrif), Jews and Christians fall somewhere between unbelievers (kafirun) or polytheists (mushrikun) and true Muslims.

What F.E. Peters says about the Koran—covered here in an excessively condensed form—is part of his broader analysis of all three monotheistic scriptures, an analysis that requires far more space and attention to address properly. But what distinguishes the Koran from the other two scriptures is that it is the only one that “enjoys a self-conferred canonicity” and “anoints itself as both Revelation and Scripture.” The Koran, Jacques Ellul remarks in Islam et judéo-christianimse (2006), is supposed to be dictated, word for word, by God. The Bible (old and new), on the other hand, is inspired by the word of God but written by dozens of people in a give-and-take fashion. It is mostly a history book, or rather the history of God’s relations with his people. The difference between the texts of the Koran and Bible may explain the reason why a literature of Koranic criticism has been difficult to undertake by Muslims, for it amounts to tampering with the word of God, even though it is quite clear that the words of the Koran were heavily edited by human hands.

Much remains to be known about the textual history of the Koran. In fact, despite the tremendous noise Islam generates everywhere, we haven’t even begun scratching the surface of its history yet. “We cannot tell when the sura divisions were introduced or who gave them their present names, which we know were not the only ones in circulation. This ignorance extends to many other areas of the text,” writes F. E. Peters. The history of the Koran “is chiefly, and very defectively, written from later literary texts about the [Koran]. And even these traditions are uncertain about many things, on how or why the names were attached to the suras or why twenty-nine of the suras open with a series of “mysterious letters” or what those letters mean.”

Will the doors of the ijtihad open to this vital field?

Salam Mr Anouar You Said, “Much of what Muslims believe is unique to the faith—such as Mohammed being the seal of prophets or besieged believers falling asleep for centuries in a cave—are ideas taken from other religious traditions. For example, centuries before the birth of Mohammed, the Iranian prophet Mani (d. 277 CE), founder of Manichaeism, synthesized elements of Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and even Buddhism to produce his own book of recitation/songs, “Psalms of Bema,” secluded himself in a cave and emerged with a “Book of Painting,” claiming to be the promised “Paraclete” in Christianity, a sort of seal of prophets.” Well, Mr Anuour, I am not going into details, but the facts is, the Prophet and the Holy Quran was well introduced during the late 3rd century and early 4th century of the common era, respectively. First off, the Prophet Muhammad was NEVER an Arab. The Holy Quran confirms that he was the direct descendent of the Prophet Yacub [Jacob] thru the family of Abraham. Read the Glorious Quran 03:33; 12:06; 19:58; 29:27; 57:26. He was the last descendent of the Prophet Ishaq from the prophetic family of Prophet Abraham. 2. Christianity begins between the 4th and 5th Century. Prophet Muhammad was born before the 4th Century of the Common Era and the Holy Quran was sent down in the 4th Century in order to counter the distortion of the 1st Book of ALLAH, which comprises of the Torah and Injeel. His main mission is to stop the distortion by the Christians as confirmed by the Holy Quran 02:79 So woe to those who write the “Book” with their own hands, then say, “This is from Allah ,” in order to exchange it for a small price. Woe to them for what their hands have written and woe to them for what they earn. I will segregate the verse into A & B A. So woe to those who write the “Book” with their own hands, then say, “This is from ALLAH,” in order to exchange it for a small price. Look at the imperfect verb, shows that the sentence in Present Tense. It proofs that the Quran was sent down during the time when a Book was written. This can only be during the Creed of Nicaea in 325CE, when the Romans under Constantine created the NT. This was the time when the distortion of the Book of ALLAH started and that is where the Prophet comes into the picture to stop the distortion, as per the Holy Quran 05:68 Say, “O People of the Scripture, you are on nothing until you uphold [the law of] the Torah, the Gospel, and what has been revealed to you from your Lord.”…… The command of ALLAH thru HIS prophet is the above verse. This shows explicitly that the 1st Book of ALLAH was intact. Nobody in their right mind would want to teach things that are already distorted! The Prophet warned the People of the Book to uphold the Torah and Gospel and the Quran for their own salvation. Unfortunately, they did not as per the Holy Quran 05:66 And if they had kept up the Taurat and the Injeel and that which was revealed to them from their Lord, they would certainly have eaten from above them and from beneath their feet, there is a party of them keeping to the moderate course, and (as for) most of them, evil is that which they do B. Woe to them for what their hands have written and woe to them for what they earn. Look at the perfect verb, shows that the sentence in Past Tense. The above verse confirms that most of scriptures of the NT were composed during 1st Century and the 3rd Century. The 4 Gospels and the letters of Paul were written between 50 and 100 CE. Again you said “The story of the “People of the Cave” is an older Roman Christian parable from the third century. The Seven Sleepers hide in a cave, near Ephesus in Turkey, to protect their faith during the persecutions of the Roman emperor Decius and end up sleeping for two centuries, awakening during the reign of Theodosius II and dying soon thereafter.” The Glorious Quran 18:22 They will say there were three, the fourth of them being their dog; and they will say there were five, the sixth of them being their dog – guessing at the unseen; and they will say there were seven, and the eighth of them was their dog. Say, [O Muhammad], “My Lord is most knowing of their number. None knows them except a few. So do not argue about them except with an obvious argument and do not inquire about them among [the speculators] from anyone.” Read the verse thoroughly and you will find that it is in imperfect verbs – present and future tense. The story of the sleepers had already been prophecised by the Holy Quran. The Holy Quran confirms that the sleepers slept for 309 year. Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire began with the stoning of the deacon Stephen and continued intermittently over a period of about three centuries. The Holy Quran confirms these. It shows that the sleepers were actually Muslims who believe in ALLAH. The Romans persecuted them for their believes during the 1st Century of the New World Order. Constantine, on taking the imperial office in 306 CE, restored Christians to full legal equality and returned property that had been confiscated during the persecution. These was the period where the original teaching of the Torah and Injeel was about to be destroyed. The earliest Christian version of this story comes from the Syrian bishop Jacob of Sarug in the 5th century CE. You Said, “Zoroastrian influences, Tom Holland shows in his book In the Shadow of the Sword (2012) shaped the new religion in surprising ways, too. They were the ones who introduced the execution of apostates, the five prayers and the use of the siwak, or toothbrush.” You are 100% right as these are UNQURANIC! You said “The geography of the Koran doesn’t make much sense if we take the traditional accounts of its revelation literally. Moreover, as the scholar F. E. Peters reminds us in The Voice, the Word, the Books (2007), the Koran could not have been written during Mohammed’s time because we have no traces of literacy in 7th-century Mecca and Medina and there were no known tablets in Arabia. Poetry was a public performance and was transmitted orally; like the Koran, it was written down in the 9th to 10th-centuries. When that happened, it was the Arabic of northern Arabia, near Syria, that was used.” In fact Gerard Puin claims that many of quranic verses may even be a hundred years older than Islam itself. And he was right. ALLAH knows best