Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook and young cyber tycoon, wants the whole world wired and every human being to have access to the Internet. To bring Wi-Fi to people who can’t be reached by a cell tower, he may rely on high-flying balloons or solar-powered drones. Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft, is on a crusade to reduce preventable deaths among children and escape extreme poverty. And physical engineering, which has been eclipsed by social media technologies, is returning to Silicon Valley to design a new line of high-tech “wearables” to improve the lives of consumers.

Culled from recent news, these activities do not make it in the pages of The Second Machine Age, a book by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, but they could have easily been cited as examples of what’s awaiting us in the coming decades. The MIT authors make it clear that our future is about to be radically altered by the rise of a digital civilization.

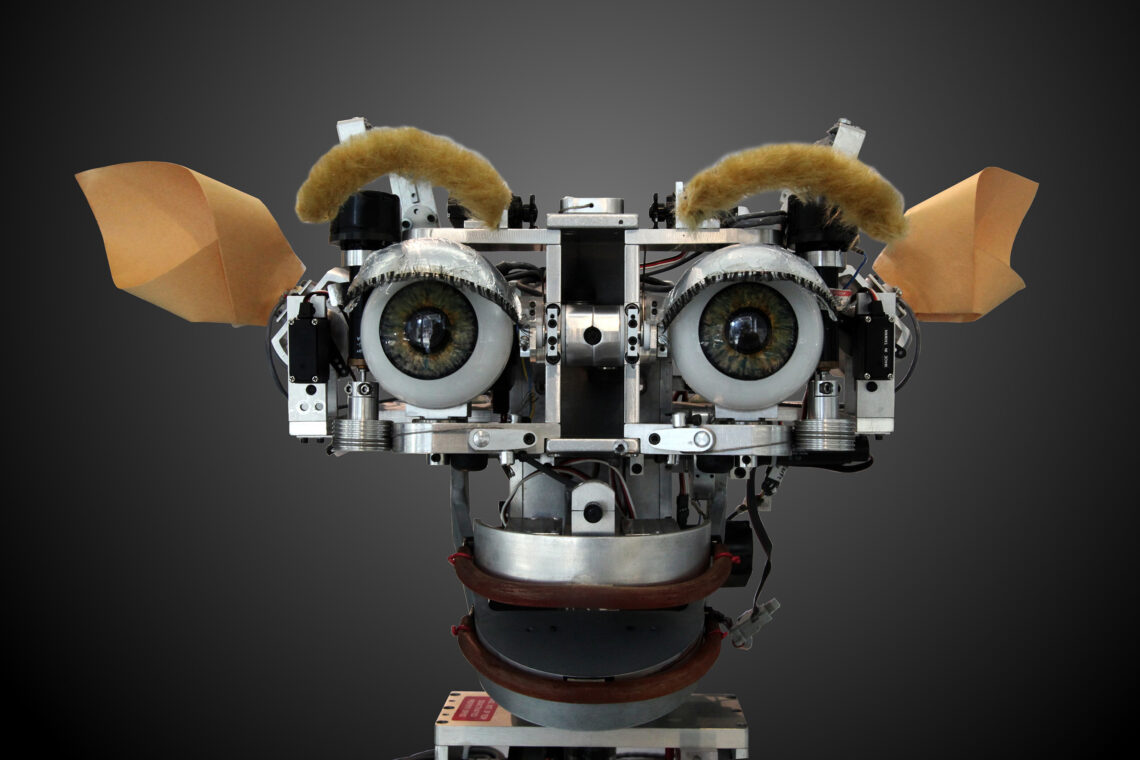

We have come a long way since we started domesticating animals, writing, farming, thinking about the meaning of life and death, and inventing religions and the modern numbering system. These, and many others, are landmark events in the long march of human history; but when it comes to a quantitative jump in the improvement of life, nothing comes remotely close to the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century (the first machine age), which replaced muscle force with steam power and opened the gates to endless production and reproduction. Electricity, the internal combustion engine and indoor plumbing—which appeared the last decades of the 19th century—were only a few aspects of the energy unleashed by this industrial age. Today, we can’t imagine our world without these inventions, even though there may still be significant pockets of people who are still not benefiting from the wealth they have engendered.

Economically, the first machine age was also the heyday of classical capitalism—brutally exploitative and politically violent when needed. Yet, ironically, in terms of inequalities, the age of classical capitalism pales in comparison to our own digital times. The cornucopia generated by the Internet Revolution has benefited fewer winners and made more people professionally redundant. In the realm of photography, Kodak can’t compete with Instagram (owned by Facebook), but Kodak, before it went bankrupt, employed far more people than Instagram does. Digital content costs close to zero and can reach an infinite number of consumers. That is not possible with physical objects like cars, even though robots have reduced human input in the factory floor to a minimum. Software is killing many professions, too. Where do these digital victims go for work? Cooking, gardening and nursing will continue to require humans, but the competition for these jobs will grow so intense that employers will reap the competitive advantage. Life in the digital age doesn’t look promising for the untrained and unskilled human.

Yet ours is a society of communes. Some of the things that educate and entertain us are generated by unpaid agents (like you and me) and are available for free. Wikipedia is the world’s largest and most comprehensive encyclopedia. We write blogs and post videos on YouTube. Google is scanning tens of millions of books and translating our languages. We connect through Skype and free email applications. There are hundreds of useful applications designed to help us that cost nothing or only a symbolic fee. This magazine is available for free to readers. We don’t offer cash for such services, but we “pay” with our attention.

Given the speed of change, it is almost shocking to recall that the World World Web was invented less than 30 years ago! Which is to say that we are still in the infancy stage of this emerging brave world. One thing is abundantly clear, though. If one adds up both ages—the industrial and digital—we are clearly heading toward a major redefinition of what it means to be human. I am not referring to increasing mechanization and digitization of the human body, but, more essentially, to how most human labor will cease to have any relevance in a production system that depends on technology. We are already in a world of material excess, but since the cornucopia is not shared fairly among all humans, the paradox of abundance and misery coexisting side by side is still causing unnecessary anguish and troubles. The dilemma of capitalism that Karl Marx expressed so succinctly in the 19th century is now amplified by the exponential powers of digitization.

Obviously concerned by an economic model that doesn’t work optimally for the social good, Brynjolfsson and McAfee recommend a new approach to education, more federal support for basic research, rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure and a tax system that discourages “negative externalities,” such as pollution, and encourages positive ones. They also support what is called a negative income tax and a value added tax (VAT) to create more balance.

For people who celebrate the powers of ingenuity, such recommendations come across as dispiritingly timid. We agree that good work is indispensable to a good life and that we want everyone to have that inherent right, but complicated tax schemes are not the best way to achieve that. The more than 1200 economists who wrote a letter to the U.S. Congress in 1968 were closer to the mark when they called for a basic or guaranteed income for all Americans. They knew, as had many before them, and many since, that automation was making human work superfluous.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee also seem to forget that we live in global world, a place where billions are still left behind. Just as cell phones improve businesses and lives, sharing a basic income, perhaps administered by a UN-type global fund, would make the world a much better place. Such a move could boost local economies, reduce conflict, stem the painful drive for migration and create a genuine global community. Companies could reap profits for decades to come, even as the global fund protects the dignity of people in an environment where production depends less and less on human labor. After all, only humans can buy what robots make.

I have been supporting the idea of a guaranteed income since 2003. If carefully designed and implemented in such a way as not to undermine the dignity of work, it could be truly transformative.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.