A few years ago, I wrote a review/commentary on The Road from Morocco, a thrilling account by Wafa Faith Hallam, a young, modern Moroccan woman who leads a truly quixotic life in search of freedom and possibilities, until, somewhat battle scarred from her peripatetic journey, she settles on the shores of Long Island, in New York, to relax in a more meditative life. I remember staying up all night to read the book, so mesmerized was I with the courage of Wafa who shattered every stereotype about Arab women. I found the self-published book on Amazon, and I later got to know the author and her daughter. I still believe that the book is one of the best biographies that I ever read and should be required reading by anyone interested in Arabs, Islam, the West, and women.

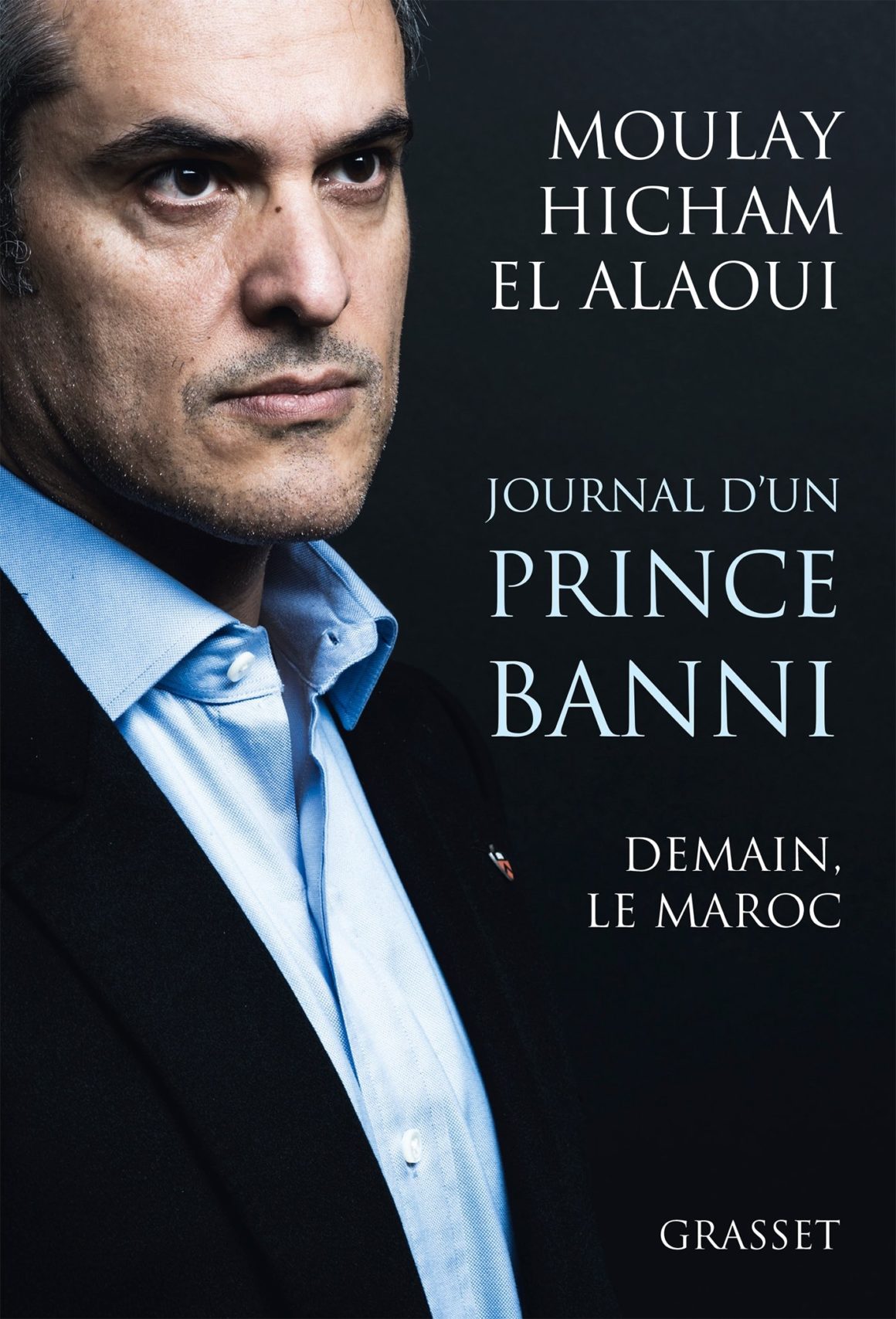

I had a bit of the same feeling reading Moulay Hicham Ben Abdellah El Alaoui’s memoirs and reflections in Journal d’un prince banni: Demain, le Maroc (Diary of a banished prince: Tomorrow, Morocco). Possessed of an iconoclastic nature and recently awakened to the brevity of human life, the 50-year-old Moulay Hicham (once third in line in the succession for the Moroccan throne) has decided to write a tell-all account about his life inside the precincts of the Moroccan royal family and, in the process, shed light on the ways of the Makhzen (traditional state apparatus) and the darwinian race by courtiers for the king’s graces. Very early on, the American-educated author warns us that he is not going to mince his words.

If that’s what he has done, the picture that emerges from this book is both unsurprising and fascinating. We read accounts of palace intrigues under Hassan II in previous books, but this is the first time a member of the royal family chooses to go public about life in the inner sanctum. Born to parents who, together, embody a big part of the power elite in the Arab world, Moulay Hicham is educated at the Collège royal, a special school set up by his grandfather for the education of princes and a select group of Moroccans gathered from around the country. But he doesn’t last long in this highly regulated environment and opts, instead, for the American School of Rabat, which launches him into the world of American higher education and its liberalizing effects. In fact, his Americanization proved to be a major irritant to Hassan II and the idiosyncratic Moroccan-French culture of the palace and the Makhzen.

Not that Moulay Hicham has ever fitted in Morocco’s conservative power circles. Hailing from one of the most powerful Lebanese families, his Sorbonne-educated mother, Lamia el-Solh, is his bridge to Jordanian, Saudi, and other Middle Eastern emirs and tycoons. In this motley group of Arabs, the prince finds loyal friends and business partners who insulate him against the vicissitudes of the Makhzen, especially after his father dies in late 1983. By the time Hassan II strips him off his royal title in 1986, the renegade prince is simply too socially resourceful and globally connected to be hurt by this exclusion.

Although he has been banished, the Americanized Moroccan prince retains a fondness for his exceptional uncle, just like he bears genuine affection for his cousin, the present king Mohammed VI. Unlike his younger siblings who are happily integrated in the royal household, Moulay Hicham finds fulfillment in his rebellion; it allows him to safeguard his autonomy, start businesses and centers at Princeton and Stanford, write articles in Le Monde diplomatique, and publish a best-selling book about his life between and across very different cultures.

Apart from the surprising insights in the ways of King Hassan II and elbow pushing within the king’s closest circles, we don’t get more than the standard claim that an executive monarchy and the parasitic class that surrounds it are relics of a fast-disappearing past. Moulay Hicham doesn’t want the monarchy to exit the gates of history yet; he just wants to see it redefine its function in a democratic society. How this would actually happen is never laid out for the reader to see. We are just told that democracy is the only way forward and that the Makhzen, with its far-reaching tentacles, must be dissolved in order to make room for a future built on healthier foundations.

Without more information about Moulay Hicham’s political views, I re-read “L’Autre Maroc” (The other Morocco), an interesting utopian story/article he published last year in the French periodical Pouvoirs about Morocco in the year 2018, that is to say, less than five years from the date of publication.

Utopias are not routinely designed to be experienced in the author’s lifetime, which is why this essay is hard to categorize. And the role of the author is not exactly clear. Is he a foreigner visiting Morocco to check on his long-planned green city, the first of its kind in Africa, near Rabat? Or is he a self-exiled Moroccan prince returning to his native country to check on the new nation that has emerged from a Cumin Revolution and a new popular constitution that has kept the monarchy but banished the ghoulish Makhzen to the dustbin of history? If the latter, why would an immigration officer ask the visiting prince about the purpose of his visit to Morocco? Such questions are not addressed to nationals entering their homeland.

Be that as it may, Moulay Hicham comes back to a radically transformed country. Morocco’s main dialect, the darija, is now the official language (at least of children entering school), although classical Arabic and foreign languages are also taught. The king is still the symbol of the nation’s unity, but people express their fealty and allegiance to their nation, not to him. The monarch has, in fact, become a citizen-king, his palaces have turned into public institutions, and the government has taken control over strategic industries. A minister of defense oversees the armed forces. There is no longer a ministry of information, and the long-banned Islamist party, al `adl wal ihsan, has risen to power. A super fast train connects Rabat and Casablanca; a metro is built in the great commercial city; and Moroccans are producing their own cars and digital chips. They have become so free and genuinely entrepreneurial that the desire to emigrate seems to have subsided.

One can’t discount Moulay Hicham’s ideas, however improbable they may sound, if only because he has invested a lifetime pondering the shape and future of Moroccan politics, including that of his dynasty. What I find perplexing, though, in this article, as in the author’s book and other statements over the years, is how he manages to sidestep or soft-pedal the question of Islam. He tells us that Islam is what unites Moroccans and asks us to imagine the possibility of a party of Muslim Democrats, similar to the Christian Democrats of Europe, but such an analogy doesn’t do justice to the complex historical evolution of Europe and the Arab Muslim world over the centuries and millennia, and does not help us in any way to discuss the relationship between deep faith and Western-style freedom in Morocco. It is precisely on the supercharged issue of Islam that Moulay Hicham’s eloquent analysis finds its limits, and it is this reluctance to address the clash between Islam and American- or European-style secular democracy that, in the end, confounds his analysis of his cousin’s role.

This is not the place to outline the different itineraries of Christian Europe and the Muslim Arab world, but suffice it to say that when Thomas Jefferson and his fellow founders were thinking about the shape of an American republic, they were well versed in the classics of ancient Greece, the history of Rome and were heirs to a long political tradition, beginning with the Magna Carta in the 13th century, the charter that defined the limits of the monarch’s power in England. It took many centuries for Europe and the West to develop a political system that Moulay Hicham considers to be a model for his homeland.

Muslims never had such traditions. Terms such as democracy and republic are alien to Islamic political thought. As in the days of early Islam, the topmost legitimating factor in Muslim-majority communities is the virtue and piety of the caliph or sultan, which is why Muslim leaders are constantly cajoling and coopting religious leaders, the `ulama. The rise of literacy in our age has only made the pressure more intense: today, any Muslim can read and quote from the Koran or the Hadith and demand the literal application of whatever he or she considers to be the sharia (Islamic law). Literacy has promoted literalism on a large scale, further entrapping Muslims within the covers of a medieval canon that leaves little room for critical thinking. How is democracy—based on individual freedom and the separation of power from religion—to enter the well-guarded fortress of theology?

This is the question haunting freedom-loving people living in Muslim-majority Arab nations. For in these societies, authoritarianism is a two-way act—political and social. Military and other forms of dictatorship are obviously political, while intense public pressure to be a “good” Muslim is social. There is little margin for diversity in such a stifling environment and no possibility for the kind of reform Moulay Hicham wishes for, since the only democratic outcome, as he well knows, is an Islamist movement that champions Moroccan authenticity, presumed to rest on the rock-solid foundations of the Koran and Hadith. Since Islam and its prophet are sacred and beyond debate, there is little room for genuine democracy, which rests on fallible human agency, political disputation, and the quest for change. All one has to do is say that the Koran and the Hadith say so and so and any attempt at democratic practice is muted and pushed back to the margins. At a time when the Boko Haram is outlawing modern education and kidnapping teenage girls in Nigeria and Sunni extremists are charging lawyers with blasphemy for the slightest of reasons in Pakistan, we can’t avoid the fact that we need strong counterbalancing liberal forces to clear the way for freedom of conscience and expression–the two main pillars of liberty.

For democracy to really hold, Islam itself must be examined in the light of history and modern knowledge. Is it truly the expression of a supernatural intervention, or a man-made Middle Eastern religion? Does the Hadith really tell the story of Mohammed, or is it a fiction designed to bolster Arab pride? Is belief in one God (Allah) and his prophet (Mohammed) the only path to a good life, or is it one of many ways people make sense of their existence? Can citizenship be totally separated from Islam in a Muslim-majority nation?

The way people approach such questions would a good indication of whether Muslims are ready for Moulay Hicham’s dream society or not. We need to recall that democracy emerged in a pagan polytheistic society, one in which gods and deities were half-human. Monotheism, with its insistence on an almighty god with the power to reward and destroy on this earth and in the hereafter, has a very different impact on a polity. In such circumstances, progressive reform depends on enlightened leadership, not the uncritical sentiments of the masses. This may not be the perfect solution, but unless we are willing to deal with our traditions, especially Islam, critically, we have no other discernible options to change or catch up with the kind of modernity Muslims crave. One can’t imagine the modern world, with its hard-earned freedoms, without the rise of the Enlightenment in 18th-century Europe. The American republic, with its divided powers, is an outcome of this earth-shaking cultural revolution.

In my view, politics are a reflection of a society’s dominant cultural trends; unless Muslims undergo a cultural revolution, one that allows people to think freely and contest centuries-old dogmas, we can’t enjoy the benefits of Western freedom. In Morocco, the main institution preserving freedom from an illiberal Islamic culture is the monarchy. (We need to recall that everything is relative and absolutes are mere abstractions.) Just like his grandfather, Mohammed VI is “le corps mystique du peuple”; he is, quite literally, Morocco’s living myth. Strengthened by the centuries-long expertise in governance acquired in dar el-mulk (house of power), the king is engaged in an extremely delicate juggling act, one that is preserving, if not enlarging, safe spaces for individualism and autonomy that could eventually give birth to a more prosperous economy and humane future.

I do understand that in many people’ minds a monarchy is synonymous with tyranny, but such a view reduces the complex topic of governance to political abstractions. This is a subject that needs serious discussion, especially in the case of Morocco, since many people, especially Americans and Europeans, do not know how to think about freedom outside of Euro-American norms. Moreover, the practice of Western democracy is in retreat these years. Low voter turnout, gridlock, the rise of xenophobic populism in Europe, and a fast-shrinking middle class (at least in the United States) are dealing a major blow to self-rule. This is not to mention the existence of Big Brother surveillance organizations that diminish people’s confidence in their political systems.

In Morocco, meanwhile, people are becoming increasingly aware of their rights (rarely of their obligations, alas!). Not long ago, I saw a policeman approach what appeared to be a homeless drug addict in a civil, unthreatening way, allowing the down-and-out young man to respond without showing any fear. The spirit of entrepreneurship is on the rise, taboos are broken on a daily basis, literary and artistic expression are becoming more daring, and many people are no longer afraid to speak out against abuses. My friend Youssouf Amine Elalami put it nicely when he told me that the Arab Spring gave birth to a new feeling of citizenship. Religious narrow-mindedness still prevails, but that, too, is gradually being challenged by filmmakers, journalists, and a few human rights activists.

Given the way Muslim-majority nations are set up, this is considerable progress, one that needs to be nurtured and supported. Morocco is unlikely to adopt American-style democracy, if only because nations have their own genetic makeups and might reject a foreign transplant. Alexis de Tocqueville, the French aristocrat who gave us the best reading of American democracy in the early 19th century, knew that such a system is not transferable to the Islamic world, because in such societies, the Koran already operates as the ultimate legislator. In this world, the sacred has a powerful, if not a terrifying, hold on people’s consciences. It is not necessarily an Orientalist putdown when people say that Arabs and Muslims are not yet ready for self-government. It is simply a sociological fact.

What Muslims have proven to be good at, on the other hand, is a lot of protests and denunciations of the Other. Their discourse is a moralistic one, privileging the pious village cleric over the suspect Western cosmopolitan. This is not a narrative of innovation and deep reform. It is the expression of people who are bereft of new ideas, whose only model for the future is an imagined golden age of Islam that is more than a 1000 years old. They consume the latest products of the West and dream of a perfect medieval caliphate.

In such circumstances, the Moroccan monarchy acts as a progressive revolutionary force, wrapping itself in the garb of tradition to introduce modern practices at every turn. Turkey needed Mustafa Kemal Ataturk to break away from the sclerotic regime of the Ottomans and steer that nation toward a brave new future, one that ultimately allowed Islamists to win at the ballot box. But the specter of reaction haunts Turkey still, caught as it is between two authoritarian tendencies. Egypt is nowadays going through the same dilemma, vacillating between the Muslim Brotherhood and the strong arm of the military. Morocco, meanwhile, is going through a gentler, more indigenous modernizing and liberating process. It is slower and less dramatic, but one that could be more stable and have longer lasting effects.

Nothing is perfect in the realm of human affairs, let alone in the arena of politics. But when one reads about atheists being charged and condemned in Indonesia, one of the most liberal Muslim-majority nations around, many of us can’t help but pin our hopes on the only model that seems to be promising real change in the Arab and Muslim worlds.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.