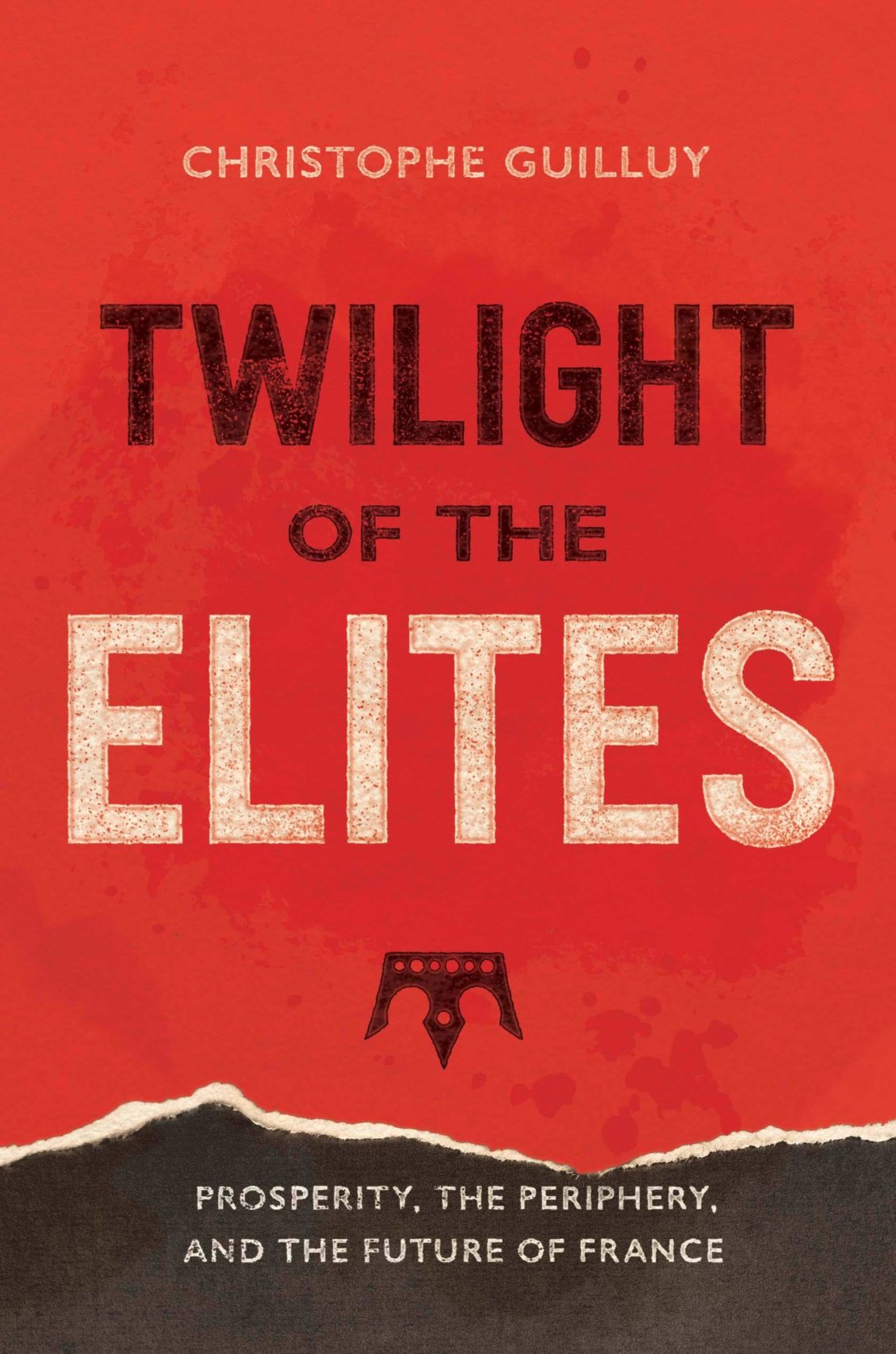

In 2016, the year Britons, eager to reclaim their sovereignty, voted to exit from the European Union and Donald Trump was ushered into the American presidency against all odds, the French geographer Christophe Guilluy published a sort of manifesto titled Le crépuscule de la France d’en haut, recently translated by Yale University Press as Twilight of the Elites. No book could have been more prescient about the shape of things to come. Noticing the hardening geographic apartheid caused by the turbulent winds of the “Anglo-Saxon model of globalization,” Guilluy saw the rising power of peripheral France, which erupted with full force in November 2018 when the leaderless gilets jaunes (yellow vests) took to the streets to protest against a fuel tax. They had had enough of neoliberal policies that had decimated their lives and made them second-class citizens in a nation that was supposed to be guided by a strong egalitarian ethos.

For Guilluy, the problem started when France became an “American” society riven by widening economic inequalities even as its elites sanctimoniously uphold the gospels of diversity and multiculturalism. While globalization and metropolization have enriched a small group of mobile elites, they have banished the rest of the country to the periphery, whether it’s the banlieues for immigrants or small towns and rural France for the majority of the white working class. It is a society “seething with tensions of every sort,” including when immigrants and dispossessed whites are forced to live together in close quarters. In this case, liberal elites, residing comfortably in their rich enclaves, add insult to injury by denouncing poor whites as racist, sexist, and fascistic, just as Hillary Clinton did when describing her rival Donald Trump’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables.” According to William McGurn’s article in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times reporter Amy Chozick asserts that this was not an unfortunate misstatement but an expression of Clinton’s worldview, one that is condescendingly shared in the “living-room chats in the Hamptons, at dinner parties under the stars on Martha’s Vineyard, over passed hors d’oeuvres in Beverly Hills, and during sunset cocktails in Silicon Valley.”

The same attitude is widespread in my own academic circles and among many of my leftist and socialist friends. Having given up on the struggle for economic justice, they have redirected their activism to promote an ever-expanding basket of identity rights, giving cover to the monochrome masters of globalization who dwell in guarded castles, shielded from view and from the vexations of having to live next door to people who have little in common with them. Blinded by their privilege, often a multigenerational one, they don’t see their ramparts breaking down and the new slaves rising to take back their countries and destinies.

Guilluy uses David Brooks’ term “bobos”—short for “bourgeois bohemians”—to describe these “hipsters” who rail against capitalism and social injustice from the safety of their privilege, while the losers of the global order sink deeper and deeper into the misery of unemployment, low wages, disappearing public assistance, and the loosening of social ties. Bobos like to talk about social inclusion but they inhabit citadels of luxury that exclude the poor and what’s left of the middle class (a “catch-all term” that actually perpetuates the fiction that the majority of people in society belong to it and therefore benefit from the economic system). Who can afford Paris or, even worse, London real estate prices? The wages of the global economic order act like massive fortresses separating the upper and lower classes since it is the market that determines where people live. Thus, globalization doesn’t lead to more openness, diversity, or multiculturalism au quotiden, but to self-segregation, “social ghettoization,” and ethnic tensions across the board. It doesn’t matter if these bobos lean left in politics and never tire of feeling bad for the downtrodden immigrant, their policies lead to the “Uberization of society” and fragmentations that deepen the fissures of social instability. Divisions are further exacerbated by diminishing opportunities for social mobility. While bobos send their children to the best schools and universities, children of the working class don’t go beyond high school (baccalauréat) and, if they do, it’s usually for a less prestigious institution or a vocational school. Bobos, meanwhile, rise to hold positions of power in the worlds of politics, media, and culture—areas where the working class, Arabs and blacks are practically invisible.

It is, therefore, not surprising that, in 2013, the bonnets rouges (red caps) would mobilize in Brittany to protest new taxes and growing unemployment. That movement, Guilluy rightly predicted, was “a harbinger of the radicalization of rural areas and small towns that now begins to make itself felt throughout the land.” The neoliberal global bobos had no idea that average French “sovereignists” were just warming up for a long fight. Guilluy could understand why Wall Street and Silicon Valley, both bastions of the global economic order, could agree on defeating Trump’s candidacy in the presidential elections of 2016. They didn’t want anyone to mess with free, unfettered trade or put curbs on immigration since the latter provides the necessary cheap labor for their citadels and keeps the indigenous white working class in check. It was on that year that Britons, having sensed that globalization only meant dispossession, voted to exit the European Union. Instead of being awakened to the bankruptcy of their ideology, global elites went on the offensive, dismissing British sovereignists as uneducated provincials. (Bobos don’t take working-class votes seriously and spare no effort to overturn the people’s vote.)

Having lost all confidence in politicians and the media, the working classes are withdrawing from the rigged global game. They have retreated into their national or religious identities, fueling yet more tensions (anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, etc.) resulting from these newly articulated solidarities. Poor whites are also fighting for their culture, their own “village”—and that’s a totally understandable impulse, whether in Morocco or France. The rejection of globalization also means “sedentism,” staying home, so to speak, since most people can’t afford expensive travel vacations and only a tiny percentage (around 3 percent) of the world’s population, for one reason or another, migrates.

In fact, Guilluy believes that “the return of sedentism is one of the most significant anthropological developments of the twenty-first century and very probably will be one of the most enduring.” It may very well be a “viable countermodel” to the flashy mirages of globalization. In such a setting, with its sense of permanence and rootedness, people could build what the sociologist Serge Guérin termed “a republic of peers,” where people “educate and assist one another in coping with shared problems.” What Bernard Farinelli called “a revolution of proximity” in his 2015 book is certainly a good antidote to the uprooting effects of globalization and may be the best weapon to fight the marginalization of the working class. After all, Guilluy reassures us, “the working class today have no choice but to defy the dominant order by taking control of their own lives.”

No one who cares about the dignity of all citizens and wants to understand the context of the growing trend of populism in Europe and the United States can afford to ignore Guilluy’s book. Hiding behind self-serving clichés about the value of globalization will only make matters worse. We are better off deploying our resources to design a truly inclusive world, one that provides for all and spares us the burning flames of a dystopian future.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.