Very often, I go through life in a state of semi-consciousness, easily forgetting important dates, what I eat at special dinners, the names of people, or even what they look like. I am always amazed at friends who remember the makes of cars and their license plates merely by glancing at them while driving. Unless it’s an earth-shattering statement that goes against the grain of conventional wisdom, don’t ever ask me about what was said and what people wore at some meeting. The situation is so bad that sometimes I’d be reading a book or watching a film and have no clue about the author/director or even the title. It’s not traumatic for me to wonder if I have some sort of dementia. I just don’t want to be around when it really happens.

Yet the crucial event that led to the writing of Second Chance in Tangier will remain etched in my memory forever. On Sunday, January 6, 2019, my friend and colleague Abdelaziz (Aziz for short) Jadir joined me for a long walk along the coast of Tangier. His goal was to continue a series of interviews he had started with me back in 2015, sometimes publishing portions in various Arabic-language newspapers and magazines. By this time, he had told me that he was writing my biography.

Aziz is one of the most prolific writers and readers I know. A novelist and a translator, he has written about the lives of the American novelist Paul Bowles (a longtime resident of Tangier), the Prophet Mohamed, and other iconic cultural and political figures in Morocco and beyond. (His book on Mahmoud Amin El Alem, the renowned Egyptian socialist writer and critic, has just been published.) I quite frankly didn’t know what to make of the attention he was so kindly bestowing on me. Strangely enough, I got used to it after a while and our walks in Tangier (and even once in Paris) became recorded discussions and ruminations about culture, politics, and our undying love for Morocco.

With his long experience in radio doing interviews with major thinkers and writers and his vast knowledge of world literature one could say that Aziz was the perfect person to probe my thinking and encourage me to pursue different cultural projects. One thing he had been relentless about from the start is for me to write a new novel. I had published one titled Si Yussef in 1992 (which, to my utter surprise, was listed by the Guardian as one of the 10 best novels set in Tangier), but after several subsequent attempts at writing more novels, I just gave up. With my family life and academic work, along with growing roles in administration at my university, I simply did not have enough time and space to dedicate to fiction. My friends and some Moroccan college students would occasionally ask me if I had plans to write a new novel, I would reply insha’allah (God willing), smile, and go back to my regular life.

Until that day in January

It was on the new marina pier that I finally relented to Aziz’s persistence, stopped abruptly, and shook his hand. I agreed to write a novel the size of Si Yussef and finish it in one year. The rest of our recorded walk was a blur. As I answered Aziz’s questions and discussed various matters with him, my mind was struggling to figure out the theme and the plot of the novel I had just promised to write.

By that time, twenty-six years had passed since Si Yussef was published. I was no longer the same person and I knew I had long lost my younger self’s insouciant voice. It was not the first time I suspected that age, conventions, and growing responsibilities had gradually constrained my laissez-faire attitude and affected my style. Besides, I had long believed (as I still do now) that deploying one’s creativity and knowledge to be fully immersed in the world is more rewarding than striving to live through one’s published or exhibited art. Undocumented pleasures may leave no literary traces, but they still lead to life-enhancing friendships and enriching human encounters, and that is good enough to make our unpredictable journey on earth a tolerable bargain.

I reached my hotel and parted with Aziz without having a clue as to what to do next. It was only when I was taking a shower that the main idea of my new novel suddenly hit me like a lightning bolt. It struck with so much force that I had to lean against the wall to avoid falling. A dark, heavy fog was dispelled from my mind, allowing the character who would be at the heart of my new story to walk confidently into the bright daylight. Who else but Lamin—the young narrator in Si Yussef—to reconnect me to the voice I had long lost? In this surreal moment, I could have been in a metaphysical realm, a disembodied man at the mercy of otherwordly powers. If this revelation was a natural occurrence in the world of art, then I count myself enormously lucky to have been touched by its spark.

When I recovered and got dressed, I took my briefcase and walked to Cafe Smara that was the model for Ashab’s Cafe in Si Yussef. Mohamed, the head waiter, was amused when I took out my laptop and started writing. (As the featured photograph at the head of this page shows, he had seen me read Si Yussef to groups of American students before and was genuinely curious about the work I was doing.) Now that I was back in the rather empty first floor of the cafe, he kept talking to me, looking over my shoulder, trying to decipher the English words I was typing and sometimes deleting to retype other ones. After a while, he walked away, exasperated by the strange ways of a Tangerian (Tanjawi in the local dialect) who had gone to America and came back like some kind of journalist, not the regular evening customer I had been decades before.

I let the waiter do his thing while I typed the first paragraph. From that time on, I just allowed myself to be guided by Lamin’s journey, happy to be his invisible amanuensis as I carried on with my regular life, dividing my time between the United States and Morocco, as I had been doing for a number of years. I had no idea who the story was written for and what would become of it after I was done. I didn’t even know what the final title would be (I tried a couple along the way). All I know is I gave myself a strict deadline to finish it. A number of waiters and baristas in different countries could testify to that!

As with Si Yussef, I could not have written this novel (which turned out to be slightly longer) if I hadn’t been under the devastating spell of my native city. One might have supposed that spending almost four decades in America would have made me somewhat immune to Tangier’s unforgiving lure. I could only wish. That’s why, in the end, I called my novel Second Chance in Tangier. All Tangerians (Tanjawa in Moroccan) in the diaspora spend their lives striving to be reunited with the city that gave them birth or adopted them. Even those who have never really left can’t get enough of it, always lamenting the Tangier that was, as if the city can only be experienced as nostalgia, a paradise forever out of reach or just a haunting memory. The enchanting but ruinous powers of Tangier are by now the stuff of legend.

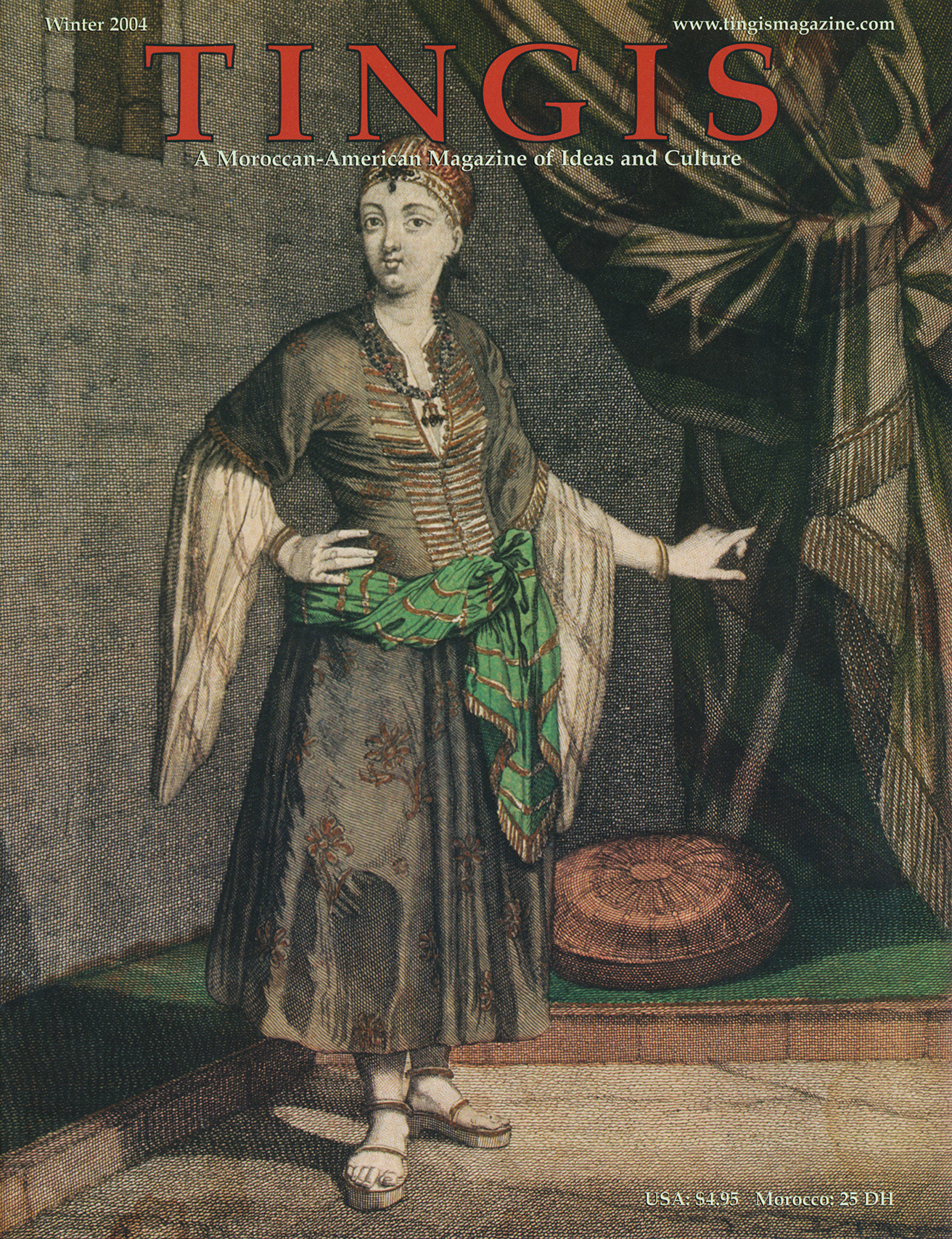

In any case, I kept my promise to Aziz, my friends, readers of Si Yussef, and, most of all, to my own memory. I am excited to be able to make this novel available through Tingis, the print magazine I co-founded with Khalid Gourad after the tragic events of 9/11 to reflect Morocco’s liberal traditions. Unfortunately, publishing the magazine on a quarterly basis turned out to be financially unsustainable. Although it eventually went out of print, I was able—with the help of Neal Jandreau, the endlessly resourceful designer and producer behind everything I have done in the last twelve years—to keep Tingis alive and free to readers. We now hope to cross a new threshold with this new book publication. As with our magazine, my goal here is to write as inspiration dictates and not worry about literary conventions, pre-packaged categories, or marketplace pressures.

Indeed, one of the reasons I wrote this novel is to address the historical, religious, and cultural issues that have long interested me in a creative or even experimental style. To launch this book-format project, I chose to start with the story of a Moroccan man and his journey in the United States and across cultures (the perennial immigrant’s tale of gains and losses in the land of the American Dream), but my long-term goal is to reflect on subjects that, in my opinion, do not get addressed to my satisfaction in the mainstream media. I did not seek pre-publication endorsements, trusting that if you read the novel and like it, you will find some way to share your thoughts about it in any forum of your choice.

You may find more information about Second Chance in Tangier on our book page.

Thank you, stay safe, and live well.

Anouar

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.