It is an immeasurable pleasure for a humanist to read Anthony Pagden’s Beyond States: Powers, Peoples and Global Order at the end of a politically tumultuous 2024 because the book allows us to imagine a world without the murderous chauvinisms that have beset nation-states for more than a century and may prove fatal in the middle term if we don’t hasten to implement more extensive and inclusive forms of governance.

Nation-states were European creations of the 19th century, designed to elevate ancient traditions of tribal kinship to a modern abstraction. The goal of a nation-state is to blend peoples with different customs and idioms into unified nations or to “mould their citizens (or subjects) into a single political, legal and cultural whole.” A nation in the modern sense consists of Volks living within the bounds of a “fatherland,” protected by a state that helps them survive and endure in a Hobbesian world.

Although we have come to associate such a construct with various forms of authoritarianism and populism, exclusivism was not the only goal of such an endeavor. The great unifier of Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini, was adamant that “the principle of nationality” was not meant to be hostile to individualism or other humans. To him, the future would comprise fully autonomous peoples united by a shared sense of humanity. Mazzini’s magnanimous voice was drowned by others, such as the German historian Heinrich von Treitschke, who believed that war strengthens nationalism and, thereby, as the English economist and political theorist Harold Laski suggested, endows states with more power. States became the most powerful tool to protect and defend the nation, even among people fighting colonialism.

Nation-states are failed projects, even compared to the empires they replaced or superseded. Islamic empires, for instance, were perfectly fine hosting diverse ethnicities, languages, and religions within their sprawling realms. The Romans had already coined the concept of “the law of nations” or the “law of peoples” (ius gentium) to acknowledge diversity in their known world. Such empires were mostly land-based and had little in common with the European overseas (colonial) empires of the late 19th century and beyond, successors to the maritime empires that emerged in the 15th century. In addition to being “the most extensive, longest-lasting of all kinds of political societies that have ever existed,” pre-modern empires “created extensive trading networks” that were essential to a global commercial system.

The nation-state confined this sprawling fluidity into narrower political concepts based on territory. However, global trade forced people out of their tribes and into the world of “sweet commerce”—in Montesquieu’s expression—and even though the European nation-state project was oppressive to others, no other than Adam Smith held up hope that the victims of international trade eventually would be strengthened by the currents of commerce to fight back against the injustices of Europeans. Like John Maynard Keynes centuries later, Adam Smith, Montesquieu, Henri de Saint-Simon, Émile Durkheim, Karl Marx, and many others thought of the “grasping, ignorant, unprincipled individual concerned solely with his own gain” as the paradoxical catalyst to a better world order, one that—for better or worse— unites humanity. There was no going back to the tribe.

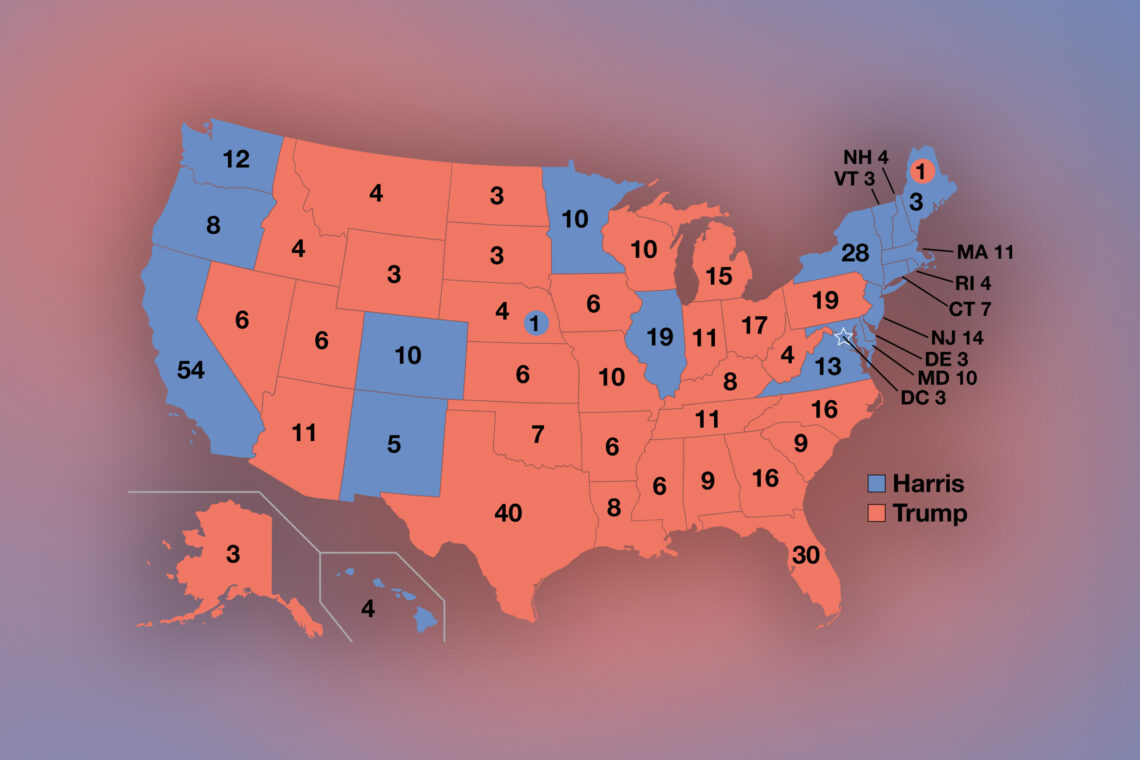

The nation-state is still going strong, but it is also beset by transnational challenges beyond its control, ones that require international treaties to manage. When seen from this prism, a better political arrangement would consist not of superstates or “a fissiparous network of supranational networks” but a federation like the European Union, the only one that exists today, and then, further down in the outreaches of time, “a federation of federations.” It may seem hard to imagine life beyond the nation-state, but such pessimism doesn’t deter Pagden: “What we have made,” he writes, “we may yet be able to un-make.”

As good as it sounds, the Roman “law of nations,” or what Jeremy Bentham would term in the 19th century “international law,” is still based on assumptions that may be alien to other people’s cultural traditions. As Cicero rightly asked: “How do you know the opinions of all nations?” Pagden knows that what passes for “international” or “universal” in the age of Euro-American hegemony is the projection of Western secular values. Still, he optimistically insists that “genesis” doesn’t have to determine “validity” forever. In this sense, he sounds much like Smith on trade and Keynes on his grandchildren’s future. However, the futures that Smith and Keynes (not to mention Marx) foresaw haven’t come to pass. Lofty as Immanuel Kant’s dream of a “world republic” or Philip Pettit’s “ideal of globalized sovereignty” may sound, such concepts can’t overcome their biased cultural “genesis” or their constitutional inability to include other social imaginaries. They also fail to account for a capitalist economy constantly evolving to forestall its demise.

Pagden knows that “the international is still politically, culturally, even legally, amorphous to most” and that most schemes for a world federation have come to naught. The historian and statesman Alfred Zimmern once thought that only “the great governing systems of the past, like mediaeval Christendom and Islam that find room for all sorts of conditions and communities and nations,” but these global religions, united by the indissoluble bonds of belief, no longer seem practical in a world with new concepts of human rights. Even the United States of Africa, the president of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, once imagined, can’t unite irreconcilable notions of governance often based on profound cultural differences. The French philosopher Alexandre Kojève was more realistic in thinking that nations could be federated only if they had shared or similar cultures. Equally problematic are the supreme courts that would adjudicate differences among federated nations, for the makeup of such courts would be highly politicized, as is glaringly the case in the United States today.

Pagden’s call for a “federation of federations” is a timely and urgent call for rethinking our identities and notions of sovereignty in a world increasingly bound by common and mounting threats. When Elon Musk, the world’s most exciting technologist, matter-of-factly envisages a multi-planetary human civilization in the not-distant future, Pagden’s proposal sounds reasonably down to earth, if only as a first step to such a cosmic destiny. Utopian as this future may sound, it is not one I would choose for myself. But then, who am I to question a world without the invented identities and imaginary boundaries that have caused endless suffering in recent history? Pagden’s heroic vision may help set future generations free.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.