His name is Gonzalo Fernández Parrilla, a professor of Arabic, Arab literature, and Islam; he has no Muslim lineage, though, but he is Spanish, and that is enough, as he notes furtively when commenting about the definition of a Moor, to make him a Morisco. After he quotes Benito Pérez Galdós asking “What is a Moor if not a Muslim Spaniard?” (Qué es el moro más que un español mahometano?), Parrilla clarifies with a somewhat sardonic but light touch that a Spaniard is indeed a Morisco, perhaps insinuating that Spanish identity is unavoidably imprinted with its Moorish heritage, despite painful but futile attempts to excise this core component from Iberian history.

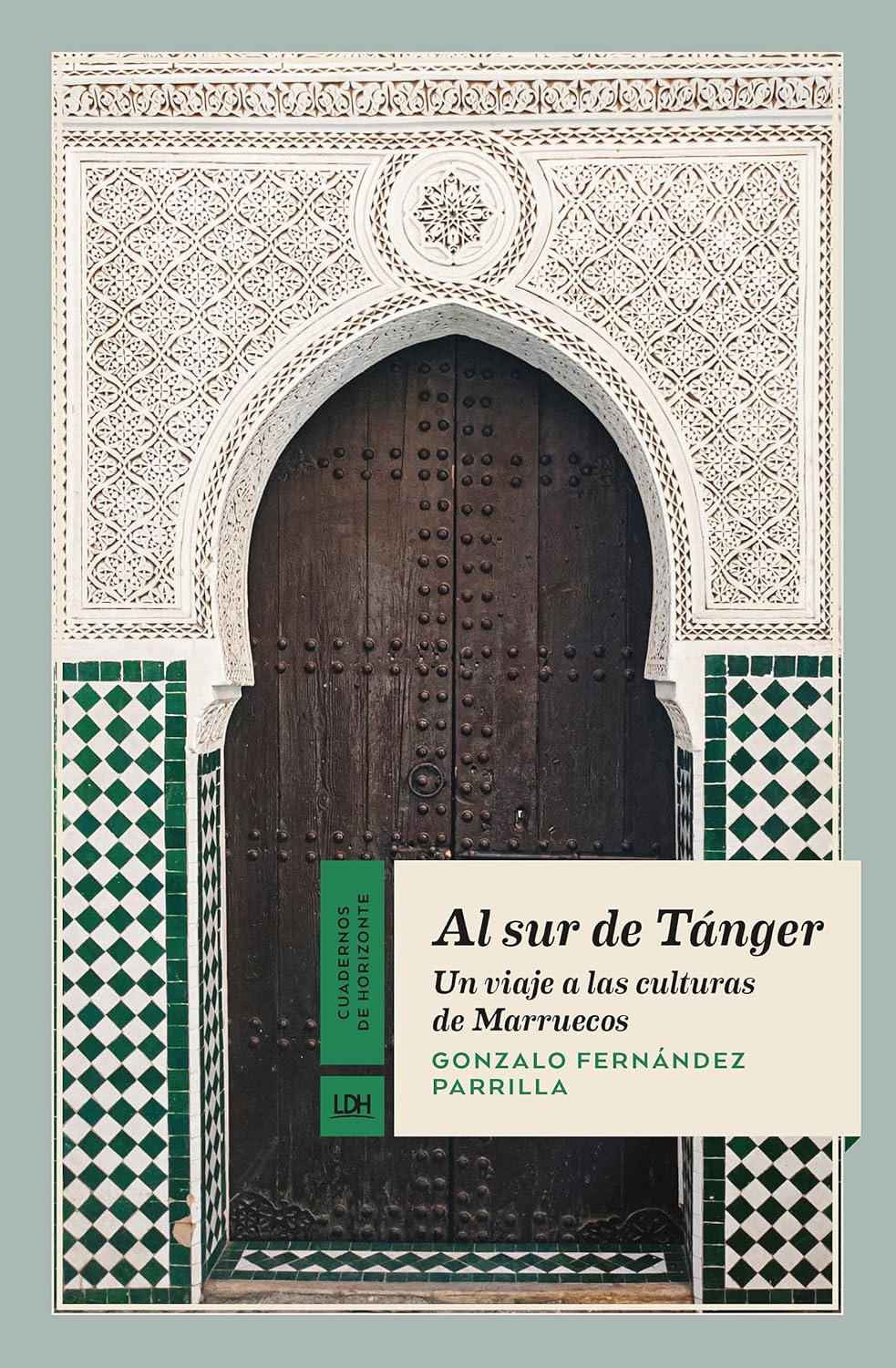

Parrilla’s book, Al sur de Tánger: Un viaje a las culturas de Marruecos, initially published in 2022 and already in its fourth edition, is the account of a very long voyage (rihla, in Arabic) to make sense of an Arab, Amazigh (Berber), and Muslim country that he fell in love with the moment he visited as a young man more than forty years ago. Like all culture clashes, his crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar, with its choppy waters and the whipping easterly winds of the Levante (known in Tangier as charqui), forced him to throw up the churros and café con leche he had had for breakfast. He recovered quickly, though, and was soon on his way to what is probably the most mesmerizing adventure of his life.

Parrilla is no Domingo Badía—better known in Morocco by his presumed name Ali Bey, the 19th-century enigmatic spy and author of Viajes por Marruecos—but an inveterate scholar seeking to understand the country he fell in love with since his fateful crossing. It almost goes without saying that Parrilla especially loves Tangier with its old Spanish ruins like Teatro Cervantes (founded in 1913) and Plaza de Toros (founded in 1950), both undergoing, after decades of utter neglect, restoration. He also enjoys a drink at the inscrutable Cosmopolita, the tiny bar founded in 1927 by the singer Antonio Sevilla.

Sometimes Al sur de Tánger feels like a visit to the juttiya, Tangier’s old flea market, not knowing exactly what piece of information or revelation awaits the reader at the next page or section. Parrilla reminds us of forgotten chapters in Morocco’s modern history, such as the remarkable fate of Mohamed Meziane, Franco’s good and loyal friend who rose to the rank of Lieutenant General in the Spanish army following the Spanish Civil War, and, after Morocco’s independence, Morocco’s ambassador to Spain. Meziane died in Madrid, shortly before Morocco’s historic Green March was launched in 1975 and Franco passed away. Meziane’s life is a shining illustration of the enduring love/hate relationship between Spain and Morocco. We must also recall that the Moorish troops and guards who helped Franco defend Spain against Communism and atheism were allowed to be buried in Muslim cemeteries for the first time since the fall of Granada in 1492.

The meticulous scholar Parrilla looks at anything that illuminates Moroccan identity. It was the French military captain Léo Morgan, as I noted in an old article, who composed Morocco’s national anthem, and it was the Moroccan poet Ali Skalli Houssaini who hastily put words to it in 1969, just in time for the soccer World Cup of 1970, in which Morocco participated. I learned that the renowned and late artist Mohamed Melehi, a founding member of the activist Casablanca Group, illustrated the first issues of Souffles, the radical magazine founded in 1966. How many Moroccans know that the great scholar Abdellah Guennoun, author of the first history of Moroccan literature, published in 1937, was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Universidad Central de Madrid? And how about macabre tracing its origin to maqbara, the Arabic word for cemetery? But the best surprise of all is to know that the best chocolate of my childhood, Maruja, was practically unknown in the Spanish peninsula and was made in Ceuta mostly for consumption in Morocco’s northern cities.

Today we tend to think of France as the progenitor of Morocco’s main cultural and sports institutions, but Spain had its own legacy, especially in Tetouan, where it established art schools and museums as well as the resilient soccer club Atletico de Tetuán, which once played in Spain’s first division, and is now known as Mogreb Atlético Tetuán.

There is so much more in Parrilla’s engrossing reading of Morocco—he covers literature, art, music, and politics with a discerning ideological eye—but, in the end, the author remains a helpless subject of Morocco and its hypnotic and ambiguous traditions, just like I am, after more than forty years of living in the United States. He and I may end up flying out of our Tangier homes, lifted by the furious easterly winds of the Levante or charqui, but we have no other place to land. For better or worse, Morocco is our only destiny.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.