No other Moroccan photographer working today has achieved the sort of international prominence that Yto Barrada now enjoys. Born in Paris to émigré Moroccan parents, raised in France and Morocco, educated in those two countries and in the United States, Barrada is a consummately global artist whose work has been exhibited in places as far-flung from each other as Birmingham and Beirut, Dubai and Chicago. No matter where her work is exhibited, however, whether in the Middle East, in England’s Midlands or in America’s Midwest, Barrada’s subject matter has been and remains resolutely local: her work dwells principally on Tangiers and its environs, although the latter can at times be read as metonym for the country as a whole. Along with the Rif mountain chain that lies behind it and the bodies of water that it overlooks, “the quaint provincial town” that Barrada calls home bulks large in all of her work not just as photographer, film-maker, and installation artist, but also as the co-founder and director of the Cinémathèque de Tanger, a multi-purpose cultural center that houses among other projects the Cinéma Rif, one of the first movie theaters in the country.

Negar Azimi: What is your work without Tangier? Or what was it before Tangier? Is there even a “before Tangier”?

Yto Barrada: It’s strange, people ask me what I will do next, meaning, When are you going to let go of this quaint provincial town as your main subject? But I am not a travel photographer. I am stuck here; it’s home, this is where I am. To me it’s as stressful and banal and everyday as New York probably is to you. I’m not exotic—I’m exhausted…Yes, my nervous system is chained to this place. I cry when they cut down a tree or bulldoze an old hospital. In a way, Tangier doesn’t exist; it changes all the time. So I guess we will stick together until they have finished paving it over. Then I will probably go work on dinosaurs in the south of Morocco.

“Tangerine Dreams and Magic in the City: A Conversation Between Negar Azimi and Yto Barrada.” Riffs exhibition catalogue.

From March 18 to April 22, 2012, the Renaissance Art Gallery at the University of Chicago hosted a sizeable traveling exhibit of Barrada’s recent work. Entitled “Riffs,” this exhibit (whose exact content varies with each venue) contained 45 photos, most of which were taken between 2008 and 2011 (although earlier photos are also on display), two films (made in 2009 & 2011), 14 posters dating from 2010, and wallpaper which lined the walls of the hallway leading up to the Gallery’s entrance and which was imprinted with the names of Tangier’s streets at independence. Besides presenting gallery-goers with this varied material, the Renaissance organized five related events (video-recordings of which can be found on the Gallery’s website at http://www.renaissancesociety.org). These events included a lively exchange between the artist herself and the Gallery’s Associate Curator, Hamza Walker, a conversation about the recent upheavals in the Arab world between Los Angeles-based Moroccan novelist and journalist, Laila Lalami, and an Egyptian political scientist at the University of Chicago, as well an engaging talk by Moroccan anthropologist Abdelmajid Hannoum (University of Kansas) on children who try to migrate clandestinely to Europe from the old port of Tangiers.

Coincidentally, part of the work on view at the “Riffs” exhibit—the 14 posters plus accompanying captions, some of them quite detailed—was also on display at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in downtown Chicago (http://www.mocp.org), as part of a larger multi-artist exhibit entitled “Survival Techniques: Narratives of Resistance.” At the MCOP, Barrada’s work occupied the whole of the second floor of the three-floor exhibit space, and took on distinct overtones from being placed in relation not just to a different overarching theme but also to the work of several other photographers and videographers from various countries. Both galleries ably contextualized Barrada’s production and the Renaissance Gallery’s poster for the event features a deft synopsis of the range and import of her work by Hamza Walker, who also hosted the ancillary events. (The poster and essay are available separately on the website.)

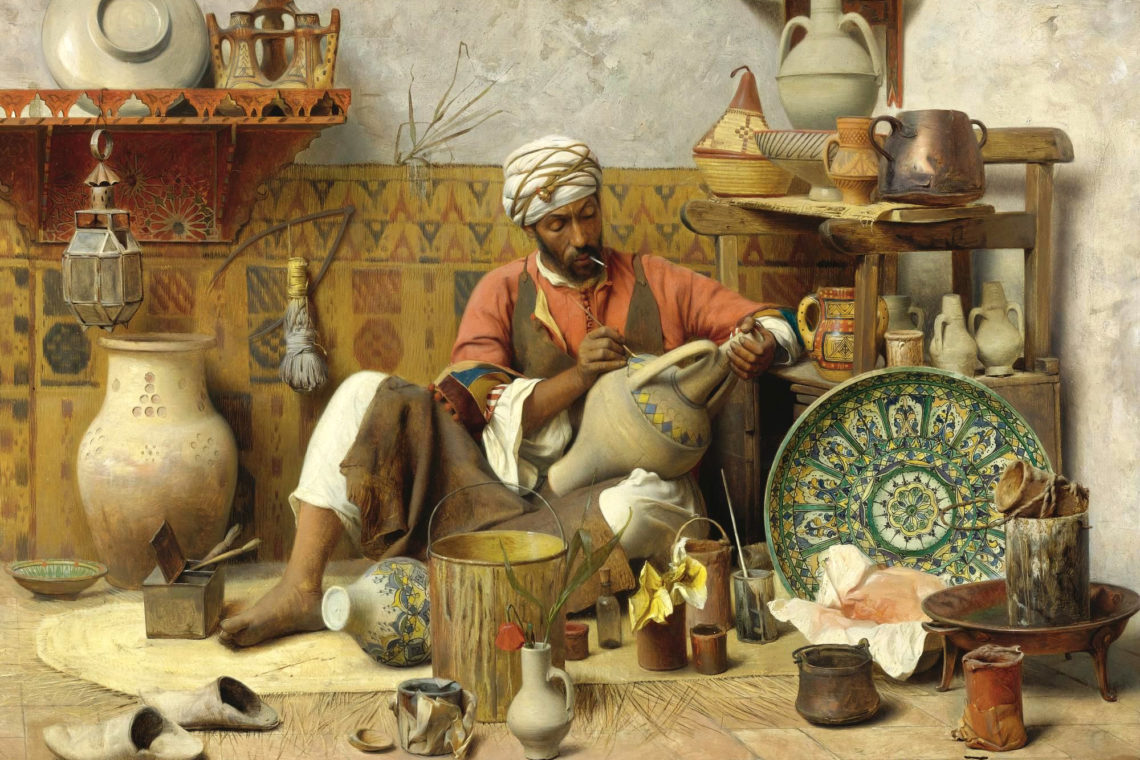

What vision of Tangier, its hinterland, and its waters emerges from these two Mid-western exhibits of Barrada’s recent activity? Possible answers to this question can be gleaned from the titles of both exhibitions, which invite viewers to consider two further questions: what might the connotations of “Riffs” be and what is it that Barrada’s work resists exactly? The artist herself suggests a response to the second of the latter two questions when she tells her interviewer in the epigraph above that she’s exhausted, “not exotic.” Few cities have been as exoticized and mythologized as Tangier. In the paintings of Delacroix and Matisse, in books by such writers as William Burroughs and Joe Orton, and in glossy brochures published by the tourist industry, Tangier has variously been portrayed as a place that shimmers with eye-catching local color, that caters luridly to illicit desires, or that can provide international jetsetters with a sensuous “Oriental” getaway a mere hop away from southern Europe.

Anyone accustomed to imagining Tangier in the light of the various myths that have enveloped it will thus be brusquely surprised by Barrada’s work, which staunchly resists any exoticism whatsoever. For throughout the past decade—during which time her hometown has been caught up in the throes of frantic growth—the photographer has frequently trained her camera on abandoned structures and vacant lots, on anonymous facades and enervated urbanites. Those photographs taken from a considerable distance, typically landscape vistas such as Route de l’unité (Unity Road/ 2001)—which The Renaissance Gallery’s Hamza Walker reads as visually emblematic of the road Morocco has travelled since independence—sometimes seem curiously affectless, and even close-up photographs of human subjects (typically taken from behind) often seem decidedly deadpan. But the frequently impassive quality of the photographs is by no means an indication of the artist’s indifference to the scenes she records or composes. In fact, the very opposite is the case, for the photographs collectively and sympathetically serve to document disturbing aspects of the price that breakneck modernization has exacted upon the city’s social and natural ecologies. Seen through this artist’s viewfinder, the luster of the “Pearl of the Strait” seems in some respects to be getting dustier and dustier.

Take, for instance, the two photographs on display at the Renaissance Gallery of a building that once served as a turn-of-the century English writer’s residence and that later was integrated into the Club Med hotel network. Taken in 2010, the two large Villa Harris photos depict different interior views of the former resort’s restaurant. In both pictures, clumps of fiberglass hang from the ripped-open ceiling and lie strewn across a dirty floor. Pieces of fabric and strips of wood also dangle unevenly from the ceiling at odd angles that belie the seeming solidity of the beams and girders that make up the building’s frame. Meanwhile, caught in the glaring light of the photo’s horizontal middle plane, the sub-tropical vegetation that must have once adorned the hotel’s grounds is now both half-desiccated and beginning to invade the abandoned structure. Duly contextualized, these two photos (along with another photo of the Villa not on view at the Renaissance exhibit) thus invite reflection on such subjects as the legacy of colonialism, the relics of the “international city” of yore (and lore), and ongoing urban decay, among others.

Such themes and formal characteristics are evident in many of the other photos in the exhibit, albeit with varying emphases. For instance, whereas the Villa Harris mini-series seems to warn prophetically of a possibly dire time to come by rendering visible aspects of a failed past, a 2009 photo, “Pallisade de chantier” (Building-Site Wall), illustrates an imagined radiant future which the present is already undermining. Implicitly calling in question the prerogatives impelling the city’s unbridled construction boom, the photo depicts a photograph of a modernist multi-storey residential building with reflecting glass facades, stylishly curved sides, and ghostly images of palm trees and of its future occupants strolling around its base. Upon closer inspection, however, this appealing vision of prospective prosperity appears to be a mirage. For splotches of rust have sprouted all along the groove that splits the two panels of the metallic building-site wall onto which the image has been pasted. Moreover, in other places sizeable chunks of the photo have peeled off or been chipped away leaving the dirty off-white metal underneath exposed. Other photographs bespeak a similar disfigurement and a parallel gap between boosterish rhetoric and imagery of progress on the one hand, and messy actualities or potentially negative outcomes on the other.

But if thus far my description of Barrada’s work has unwittingly made it sound unduly somber let me note that her recent production also gives evidence of playfulness and beauty, even if these facets of her work are also laced with a sharp sense of irony. As Okwui Enwezor rightly observes in one of the three essays featured in the catalogue that accompanies the series, a pronounced ludic streak has made itself manifest in some of Barrada’s most recent interventions, such as the double poster series on display at both the Renaissance Gallery and the Museum of Contemporary Photography. One of the posters, for instance, bears a reproduction of an official photographic portrait of Marshall Lyautey, Governor-General of the French Protectorate in Morocco in the early 1900s. To the left of the colonial official’s forbidding mien, the artist has placed a picture of a mustache along with a scissors and an invitation to “pin the moustache on the Maréchal.” In a different, yet also whimsical register, Couronne d’Oxalis/ Oxalis crown (2006) presents viewers with a portrait of a boy who occupies the photo’s foreground and who sits on ground that is framed by the trunks of two pines in the background. Dressed in blue jeans and in a turquoise shirt, the boy looks straight at the camera with his left eye, his right eye concealed by a woven crown of bright yellow blooms that sits fancifully atop his head. (An art historical side note: the boy’s insouciant air and crown of flowers recalls Caravaggio’s “Bacchus.”)

Barrada herself has insisted that her photos do not depict happy or pleasurable scenes, and for the most part the two exhibits bear out this assertion. Nevertheless, an austere beauty characterizes many of her photographs, even ones that depict or allude to undeniably ugly realities, and for this viewer at least this formal austerity imparts a certain visual pleasure. (The arrangement of the photographs at the Renaissance Gallery emphasized both their individual aesthetic power and the harmonious way in which the photographs’ motifs and compositional features often echo one another.) Sometimes, a given photo’s beauty is primarily a function of its subject, as in “Issagen—dans la forêt de cédres, Rif/Issagen—In the Cedar Forest” (2002), for instance. More often than not, however, the aesthetic appeal derives from purely formal considerations, such as the manner in which a composition’s assorted lines, volumes, and tonalities convey a sort of sober consonance, as they do for instance in Murs Rouges (Red Walls) figures 4 & 5 (2006).

And the word “composition” reminds us that for all their referential and demythologizing thrust, the photographs, videos, posters, and installations that Barrada has assiduously produced from the mid-90s to the present are not transparent recordings of unmediated reality but complex representations of it, ones that the exhibit at the Renaissance invites as to think of as “riffs,” that is to say, as performances keyed on artful repetition and occasional improvisation. Moreover, in the context of Barrada’s oeuvre the word can also be taken to connote a pluralist understanding of Tangier and its Riffian environs: there is not just one Rif, this artist’s work shows us, but many, just as there are multiple ways of representing it/them. Indeed, several works explicitly engage questions of representation and identity, such as the short video on view at the Renaissance, “Hand-Me-Downs,” in which the artist delves into her family history by piecing together unverifiable stories told by unreliable narrators and illustrated with strangers’ home movies and archival footage from the past half-century in Morocco.

In viewing these exhibits one gets the sense that one is witnessing an artist engaged in the process of articulating a coherent language with which to address not just this or that discrete issue but a whole welter of intersecting and colliding realities, the portrayal of which often exceeds the sum of its thematic parts to achieve a striking visual eloquence. Consider, for instance, the tersely named “Dolphin” (2002/2011). Commentators on Barrada’s work frequently point out that her art partly depends for its effect on the oblique and ambiguous manner in which it addresses thorny subjects and themes. At first blush, this particular photo would seem to indict the kind of ecological despoliation to which much of Barrada’s work alludes in a more obvious fashion than is the case with such works as Irises (2006), in which a few of the eponymous plants—whose local species, Iris Tingintiana, is threatened with extinction, a topic to which Barrada has devoted an entire project—are shown not yet in bloom in the middle of a grassy and weedy patch.

Depicting a dead dolphin whose blue and purple skin is flaking off like so much old paint (and echoing thereby various photos of peeling facades), the photo would seem to want to elicit an immediate reaction of pity from the concerned viewer. Yet, even as it lies beached on its left side with its small right flipper pointing incongruously at the sky (which lies outside the photo’s frame), the corpulent creature presents us with a series of mysteries rather than with definite indictments. First, why is it there? Did it die from natural or unnatural causes? Was it killed by one of the many craft that pass through the Straits of Gibraltar, often at high speed? Did a predator kill it? Second, where is “there,” exactly? All the photo depicts is the lifeless animal occupying the frame’s middle vertical plane, a patch of sandy beach around it, and the hoof-prints of another creature that has walked around it. In not providing answers to two of the puzzles with which it confronts viewers, the photograph leaves us with a third enigma, that of the expression on the creature’s face: jarringly, the sharp-toothed rictus into which its countenance has set makes it look as joyful as if it were cavorting out in the open sea.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.