The vast majority of people in the Christian and Muslim world know very little, or nothing at all, about the history of the Jewish communities in the Muslim world. The only thing most Jews know about this 1400-year history is that Jews in North Africa and the Middle East were not persecuted as much in Muslim countries as they were in European Christian ones.

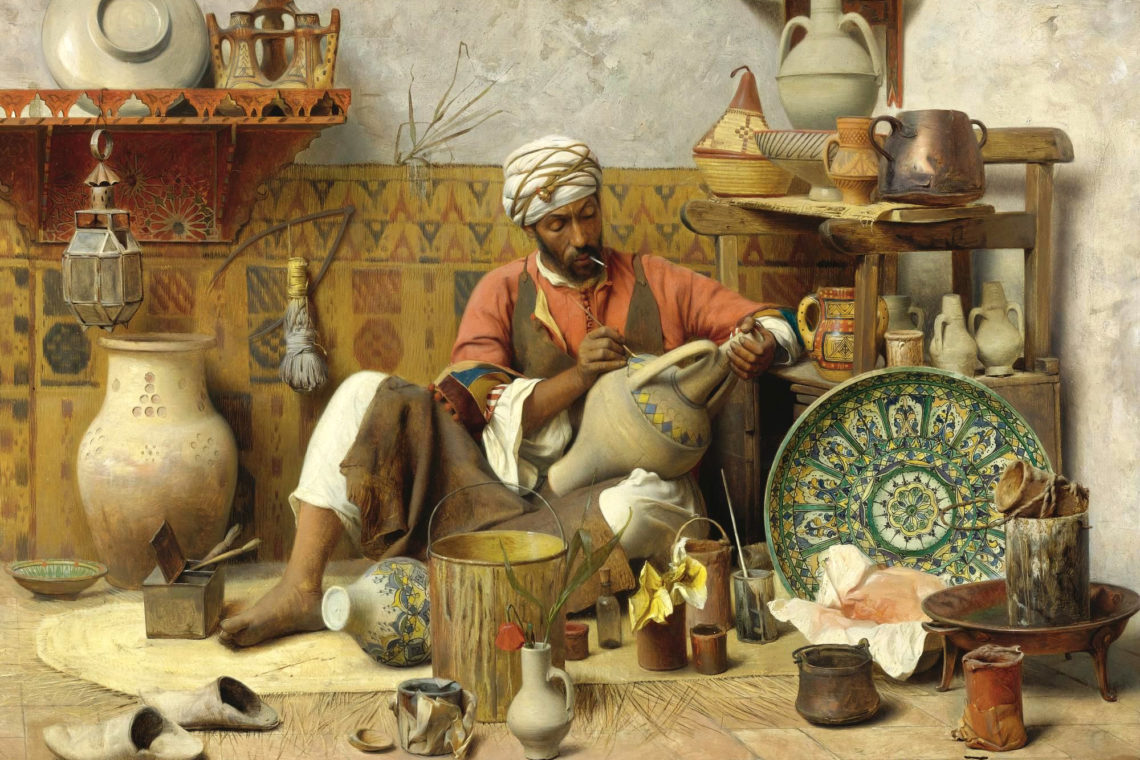

It would be a major mistake to judge from the Palestinian-Israeli political conflict in the 20th century that Jewish-Muslim relations have usually been poor. The opposite is true. Prior to the rise of secular political nationalism in the last half of the 19th century and the rise of politicized religion within Judaism and Islam in the last half century, Jewish-Muslim relations were usually characterized by neighborliness and amity. Yes, amity, as the North African Jewish celebration of Mimouna (pronounced Meemouna) shows.

The North African Jewish festival of Mimouna, a 24-hour food-centered celebration, begins right after the week of Passover ends. For many centuries, Moroccan Jewish homes were emptied of leavened bread and flour during the week of Passover. At the end of the week of Passover, Jews could eat leavened bread and pastry again, but they had no ordinary flour at all in their homes to bake with. Ashdod resident Shaul Ben-Simhon, who immigrated to Israel in 1948 at age 18, said that in Morocco the holiday brought Jews and Muslims together each year. “Our home was open to everyone, including Arabs,” he said. Ben-Simhon recalled the tradition of Arab neighbors bringing flour to his home, so his mother and grandmother could make baked goods.

Often this was the same flour that Jews had given to their Muslim neighbors a day prior to the start of Passover, so Jews could rid their homes of leavened flour, prior to Passover. When, after the end of Passover, Muslims came to Jewish homes to return the flour, they were always invited to stay for a few hours and enjoy the soon to be baked goodies. Thus, Jewish homes were filled with neighbors, friends and family exchanging traditional Arabic blessings of good luck and success while awaiting the laden trays of delicious Mimouna baked goods. The celebration often was repeated the next day with even more pastry and joy.

In Israel, unfortunately, for the first two decades of statehood, the festival was hardly observed at all. “In the early days of the state, we Moroccans were busy with absorption and working hard, often in construction. We didn’t have the energy or self-confidence to celebrate Mimouna,” said Ashdod resident Shaul Ben-Simhon. That changed in 1968, when Ben-Simhon, at age 38 and a high-ranking official at the Histadrut, Israel’s trade union alliance, organized a Mimouna celebration in Lod in a bid to help the integration of Moroccan immigrants into Israeli society. His effort to raise the community’s morale attracted 300 participants. The next year, Ben-Simhon moved the celebration to Jerusalem, got then-mayor Teddy Kollek’s support, and managed to draw a crowd of 5,000. This grew into a major celebration in Jerusalem’s Sacher Park that today draws over 100, 000 people. This event inspired the revival of Mimouna all across Israel.

Across the country, Moroccan Jews and Israelis of all ethnic backgrounds flock to smaller public and private celebrations. A special law even requires bosses to grant employees unpaid leave on the day of Mimouna, if they want to carry on celebrations from the previous evening. Since the Torah states that a Jewish home must not contain any leavened bread during the week of Passover, many Jews “sold” their regular household flour to a non-Jewish friend or neighbor, who then “sold” it back after Passover. Unfortunately, the Orthodox Rabbinical bureaucracy has arranged for a formal “sale” of all the leavened flour in the state of Israel to a few Arab Muslims or Christians, so the much more personal, private transfer to one’s Arab neighbors rarely takes place today in Israel. Perhaps, a restoration of this part of the Passover tradition will help bring Jews and Arabs in Israel closer together. Ben-Simhon believes that Mimouna promotes unity between families and neighbors. (In Morocco, it was a day when people would visit each other to bury grudges.)

There are several theories regarding how the celebration got the name Mimouna. I think that it comes from the Arabic word Amina and the Turkish word Emina that sound similar to the Hebrew word Emunah. Indeed, Emin, Emina and Ahmina are names in Turkish and Arabic, meaning a faithful or trusted one. Jews trusted their Muslim neighbors to guard the flour faithfully during the week of Passover from becoming impure, and their Muslim neighbors always did so.

Perhaps the revival of the Jewish-Muslim celebration of Mimouna in Israel could stimulate Muslims and Jews in other parts of the world to reach out to each other and share traditional pastries made from both leaven and unleavened flour. Passover starts on the evening of April 3, 2015 and ends after sundown on April 10 for all Jews in Israel and for Reform Jews worldwide, and on April 11 for Orthodox and Conservative Jews outside of Israel.

It would be wonderful if Jewish and Muslim groups or individuals invited each other to this “Celebration of Muslim-Jewish Amity.”

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.