I was perhaps 13 or 14 when I first met Muhammad Asad, alias Leopold Weiss, the distinguished journalist and author of The Road to Mecca (1952)—a memoir of his mid-century travels in the Middle East and his conversion to Islam. He and his wife Pola—her Muslim name was Hamida—had invited my parents for afternoon tea. Their house was located in the verdant Djemaa-El-Mokraa neighborhood in Tangier, also known in my hometown as “la nouvelle montagne”—amidst pretty oleander hedges and dainty bougainvillea, not far from a charming neighborhood mosque. I had tagged along, an only child more accustomed to the poised company of adults than the clamor of my peers. I recall the cultured atmosphere of their residence, its outer walls bathed in suffused light and the interior draped with wall hangings that traced the arc of his travels by camel in the Arabian Peninsula. I recall Asad’s ascetic features, framed by a delicate beard, and his wife Pola’s milky face, pierced by intense, small blue eyes. And then there were their dogs, two fleecy white Afghans. The name of one of them—Shamshir, sword in Farsi—is still inscribed in my memory. So is the taste of the cake we were served—gâteau Reine de Saba or Queen of Sheba cake—and the smoky flavor of the Lapsang Souchong tea. All together these fill my senses with the allure of exotic lands.

Muhammad Asad figures prominently among the pantheon of distinguished Orientalists at the heart of Compass, Mathias Enard’s enthralling novel, newly translated after winning the 2015 Prix Goncourt in France. This literary tour de force is foremost an in-depth probing of Orientalism—the spell cast by the Orient in Western eyes—in the 21st century. Its refutation of the idea of cultural purity makes it a conspicuously urgent text for our times.

An audacious endeavor both aesthetically and intellectually, Compass glides through multiple genres. It is at once a travelogue to the Orient in the tradition of François-René de Chateaubriand’s Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem (1811), a biographical exploration of the lives of famous Orientalists, a lucid account of past and current political stakes in a much-disputed region, an encyclopedic treatise on Oriental music and poetry, and an elegiac ode to Sarah, the hero’s unattainable beloved. Lastly, Compass is an epistemological recasting of East and West, a prolonged dialogue with and subtle recalibration of Edward Said’s seminal Orientalism.

Enard’s prose is no less exhilarating—pulchritudinous, opulent, lavish with exactitude. The reader visits regions of munificent digressions and lands of vast erudition. The opulent language finds a perfect match in Charlotte Mandell’s minute translation. While the book is well versed in musicology, it also has a distinctive cadence of its own. Enard’s looping sentences spiral like zikr, the hypnotic Sufi rhythm, which “sticks to your ear and keeps you company for hours,” enveloping the reader in its bosom, blurring time and space.

Enard’s previous novels have been compared with Balzac’s 19th-century omniscience or the modernist James Joyce’s dense textures, but Compass has a distinctive Proustian mark, if only in its insomnia motif or its utter rescinding of time. The novel unfolds during a long sleepless night for Franz Ritter, the narrator. As in In Search of Lost Time, time here eschews linearity. Past, present, and future are abolished, one night spanning the duration of twenty years. Dreams and realities collapse and commingle. Memories and anticipated moments mesh in a copious stream of consciousness.

Enard has wielded this device before in Zone, his celebrated 2008 novel, which took place during a nighttime train ride, used as a slate for the narrator’s ruminations as well. Here, however, it is less contrived, more organic than in Zone, which relied on the formalistic prowess of a single sentence stretching from beginning to book’s end.

Franz Ritter is a Franco-Austrian musicologist who specializes in Oriental melodies. Ridden with insomnia, afflicted by a mysterious and fatal illness, and addicted to opiates—a legacy of his travels to the East, he is an anti-hero, a misfit and a spurned lover, alternately melancholy, hypochondriac and sickly, in the vein of 20th-century pusillanimous narrators, like Marcel himself. Frequently quoting “Maman,” who still sends him off to his travels with a shoehorn, soap, washing powder, and an umbrella, he is an incorrigible mama’s boy, bittersweet in his self-deprecating humor and gently laughable in his defeats. He is oftentimes lost, confused, disoriented.

Like Xavier de Maistre who wrote Voyages around my bedroom (1794), a parody of the grand travel narrative, Franz journeys a great distance while ensconced at his own desk, employing “the djinni Googgle” to trace, in one instance, Sarah’s minute movements in Sarawak, Malaysia, where she is conducting research for her scholarly work.

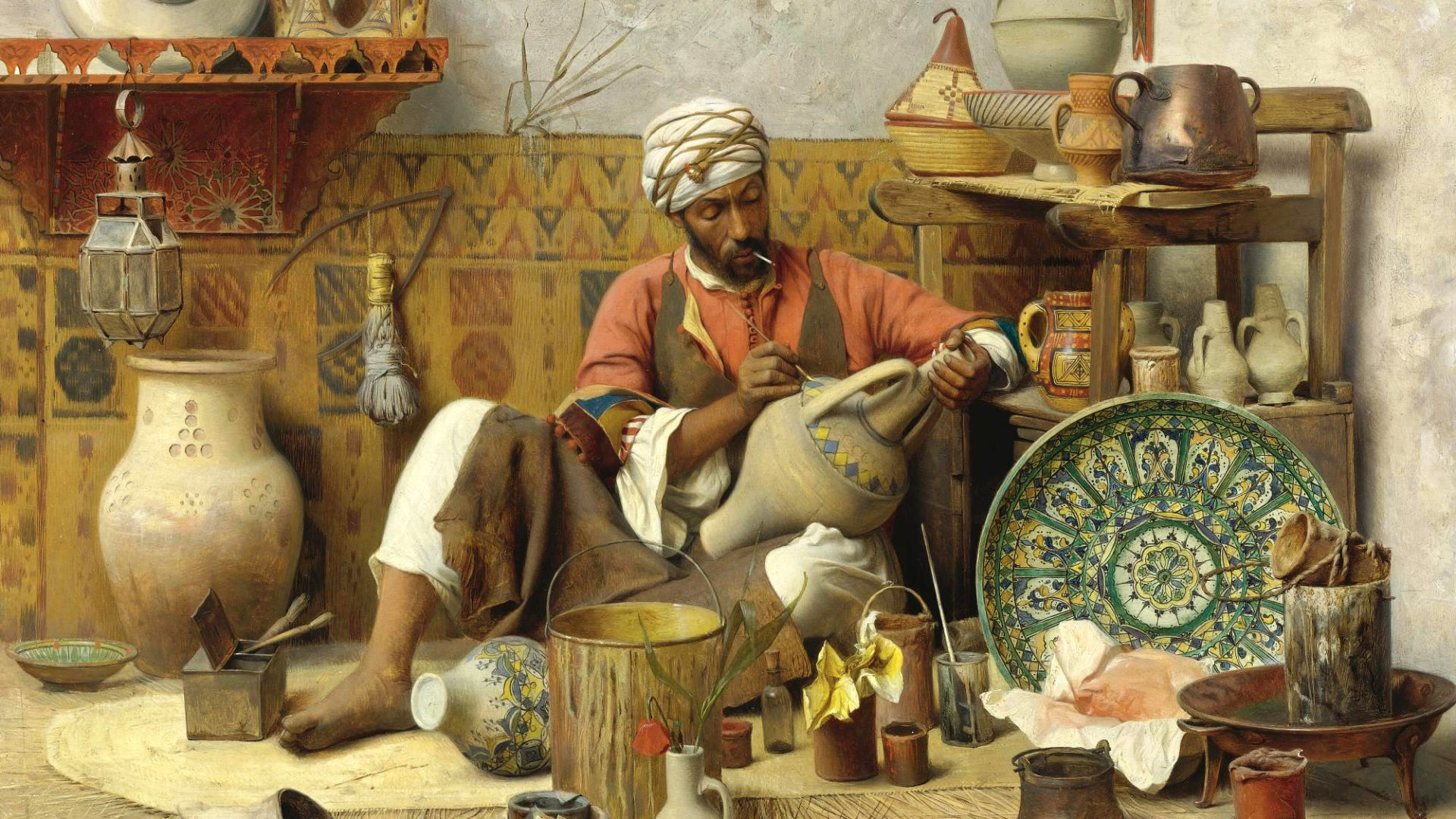

Ritter’s evocation of famed, if forgotten Orientalists has an epic breadth. We read about Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), the first great Austrian Orientalist, a translator of One Thousand and One Nights, of Diwan by the Persian poet Hafez (b.1362), and Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), with whom Hammer-Purgstall translated Roumi. We pursue, breathlessly, the trail of Lady Jane Digby (1807-1881), an early feminist who escaped Victorian England to find love in the arms of cheikh Medjuel el-Mezrab in the desert between Damascus and Palmyra. We palpitate at Ritter’s account of the adventures of Marga d’Andurain (1893-1948) in the French Levant of the 1930s. And there, of course, is the charismatic Muhammed Asad (1900-1992), the very man I met in adolescence. Here I am immersed in his back story—a Jewish Viennese journalist for the Frankfurter Zeitung who was entranced by the Muslim call to prayer, drawn by the immanence of Islam and the humility of Bedouin life in the desert, and ultimately converted. This is an Orient of culture and refinement, poetry and wine, which has bequeathed so much to the West. Pointedly, one of the book’s crucial scenes takes place in Palmyra, where the novel’s main characters enact a Maqâma, a noble genre in Arab literature, taking turns to speak about a given topic. As a locus of sophistication, it is grimly juxtaposed to today’s Palmyra, twice taken in recent years by the “Islamist demolishers” of ISIS. (It is currently under restoration after being seized again by the Syrian government).

A key question runs nonetheless sotto voce throughout Enard’s evocative summations: Were these men and women perhaps nothing other than instruments of the West’s ideological domination of the Orient, as Edward Said fiercely claimed? Aren’t Enard’s biographical vignettes veiled Orientalist clichés themselves: of lust, homosexuality, espionage, knowledge as power? Lastly, didn’t these nomads’ calling “owe a great deal to the fantasy of colonial life,” as the narrator suggests, anticipating criticism?

A compelling rebuttal is provided by Sarah, both Franz’s dazzling alter ego and luminous beloved, as bold in body and adventurous in spirit as he is timid. Sarah is French, but her Sephardi ancestors originated from Turkey via Algeria, so she partially embodies an Orientalist fantasy by reenacting the trope of “la belle juive” (literally “the beautiful Jewess”), which hails back to Salome and Rebecca in Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

However, like Enard himself who studied Persian and Arabic, she is an indefatigable analyst of the Orient, fittingly distilling the book’s ultimate wisdom (traditionally, Mediterranean and Levantine Jews were the close companions and interpreters of Islamic culture). Orientalism, contends Sarah, embodies “a need for otherness as an integral part of the self, its fruitful refutation.” If the Orient has fascinated for centuries, it is because it enabled us to escape from ourselves, investigate the idea of difference, probe the self within the other. In other words, she concludes, “Orientalism is a humanism.”

Enard is assuredly tearing at the limitations of Said’s model. Said, whom he daringly calls “the wolf amidst a flock of sheep,” and “the Devil in a convent of Carmelites,” was right, he believes, in identifying the ideological underpinnings of Orientalism, but wrong in invariably extrapolating them, without considering the individuality of each of his exemplars. By so doing, he ended up “fabricating a general discourse which becomes in turn an ideological construct, a theory which finds in itself its very vindication.”

Instead, posits Enard through Sarah, we must revisit history as one of diversity and common sharing. East and West do not occur as competing narratives. Rather, the history of this binarism rests on the porosity of their outlines, on a continuum of cultural hybridity and mutual borrowings. Exposing the mirage of purity, which he wittily dissects as “the Wagnerian illusion of the Whole,” he correctly points instead to a cosmopolitan syncretism alive for centuries. He illustrates, for instance, what Western music and literature owe to their Oriental counterparts. Or the many guises in which Oriental culture ironically began “Orientalizing” itself in response to Western desires. Thus was “Orientalism” born and nurtured.

I think here of myself on that afternoon of my adolescence, an “Oriental” by all possible standards, raised in Morocco after generations of my ancestors, and still susceptible to the lure of Muhammad Asad’s Orient. To each her Orient.

Rather than either idealizing or vilifying it, Enard concludes we must recognize it “is an imaginal construct, a series of representations, where each one of us, wherever one is, draws at leisure.” In other words, inasmuch as they are both fabrications of our own, East and West do not exist.

Enard’s Compass is thus a remarkable love letter to the Orient. Its greatest flaw, and also its greatest strength, is that much to our enjoyment, it succumbs to Orientalism while unmasking its mechanisms.

Significantly, the novel climaxes in a torrid embrace between Franz and Sarah. This rendering of their first and only lovemaking, an exquisite exercise in eroticism, captures the heart of the novel. Exploring the body of his beloved in Tehran in fleeting and lyrical snapshots, Franz conjures up the metaphor of imaginary voyages. It is love, he and we discover, love as both an impulse to forget oneself and to conquer otherness empathetically, which stands for Enard as a metaphor for Orientalism. Love, and not ideology. Enard entreats all of us to reset our “compass,” remediate the current state of “dis-orientation” of the West, and seek the Orient once again.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.