Occasionally, I come across remarkable Americans who remind me of the spirit that has made the United States an exceptional nation, one that has injected an earthshaking dose of heroism in the human experience and transformed world history for good. When such moments happen, when I actually meet such people in person, I drop everything and turn into a sort of chronicler, one who can’t contain his luck in being in such a privileged situation.

This is what happened to me today with Kevin, a 64-year-old painter and drywall contractor and repairman. Kevin had spent three days in our basement, where the pipes had burst in early January, damaging floor and walls. As he was finishing his job, I asked him to do a few touches on our kitchen wall. When he got upstairs to start that task, our brief exchanges took a different turn. I can’t remember what prompted that—when he told me that he and his wife were peace activists or when he revealed that he doesn’t have an email account.

Kevin didn’t want to be misunderstood, even though he admitted he was a Luddite. He compared dependence on technology to climbing a ladder and kicking the step below, so that one has no chance of going back. “I respect technology,” he explained for clarification, “but I respect it like I respect a viper.” It interferes with the creative process. He told me the story of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche whose later writing was affected by his use of one of the earliest commercialized typewriters (whether Nietzsche’s thinking grew mechanical as a result of this I don’t know). His wife of 27 years, I found out, spends her time wrestling with the problem of God and moral evil and is a big fan of Nietzsche and the Dutch philosopher Spinoza, while he, Kevin, is now going through the oeuvre of Carl Jung because he looooves myths and archetypes.

Who is this vegan talking about Nietzsche, Spinoza, and Jung on a step ladder in the middle of my kitchen? As we talked, I began to draw a life journey that goes something like this:

Kevin grew up a Mormon in Utah but didn’t know what to do after high school. He liked psychology and he also wanted to be an auto mechanic. His parents, like most parents, advised him not to be a flunky and get a college degree. After spending two years on a Mormon mission to the Navajos (he still speaks Navajo), he enrolled in psychology and switched to accounting. For seven years, he worked as an internal auditor and comptroller over a group of hospitals, but he hated his job and lost faith in the doctrines of his Church. So, he dropped both and returned to college to study philosophy. He now realizes that if he had to do his education all over again, he would major in the humanities and the liberal arts. He was encouraged by a professor to do graduate work, but that path felt like the same trap accounting was. He wanted his intellectual life to be an avocation, not a profession. Otherwise, things turn cerebral and all the pleasures of free thought are lost to practical considerations. Besides, he enjoys manual work too much to settle for a life of writing. And so, once again, he ran away to a life of freedom.

He worked as a bartender, carpenter, and drove around with a dog in a truck to build and repair. He was in heaven. By the late eighties, he transitioned to his current trade. It was about the same time he met his current wife (originally from Massachusetts) and followed her to Maine.

At one point in the conversation, Kevin confessed that he no longer thinks like an American and that he feels more like an ancient Greek under the spell of the Fates. Duty, he realized, is his purpose in life. Watching him on that ladder, I could see what he meant. He also lamented the lack of skilled tradespeople in the United States, praising the superior German educational model in this regard. Was he the last of a special breed?

I don’t know why I grew concerned about the future of a man who has chosen not to drive a car on weekends. I asked about his age and whether he has prepared himself financially for retirement. To assure me, he told me that he expects some income from the rental of three houses back in Utah, enough to secure him and his wife (who called during our conversation to check on him) a decent life. “I don’t need much,” he said. I asked if I could hire him to build a few bookshelves, but he told me that he had dropped carpentry many years before and that I would be better off with a good carpenter. How about painting or repairing a drywall? “Sure. You have my card.”

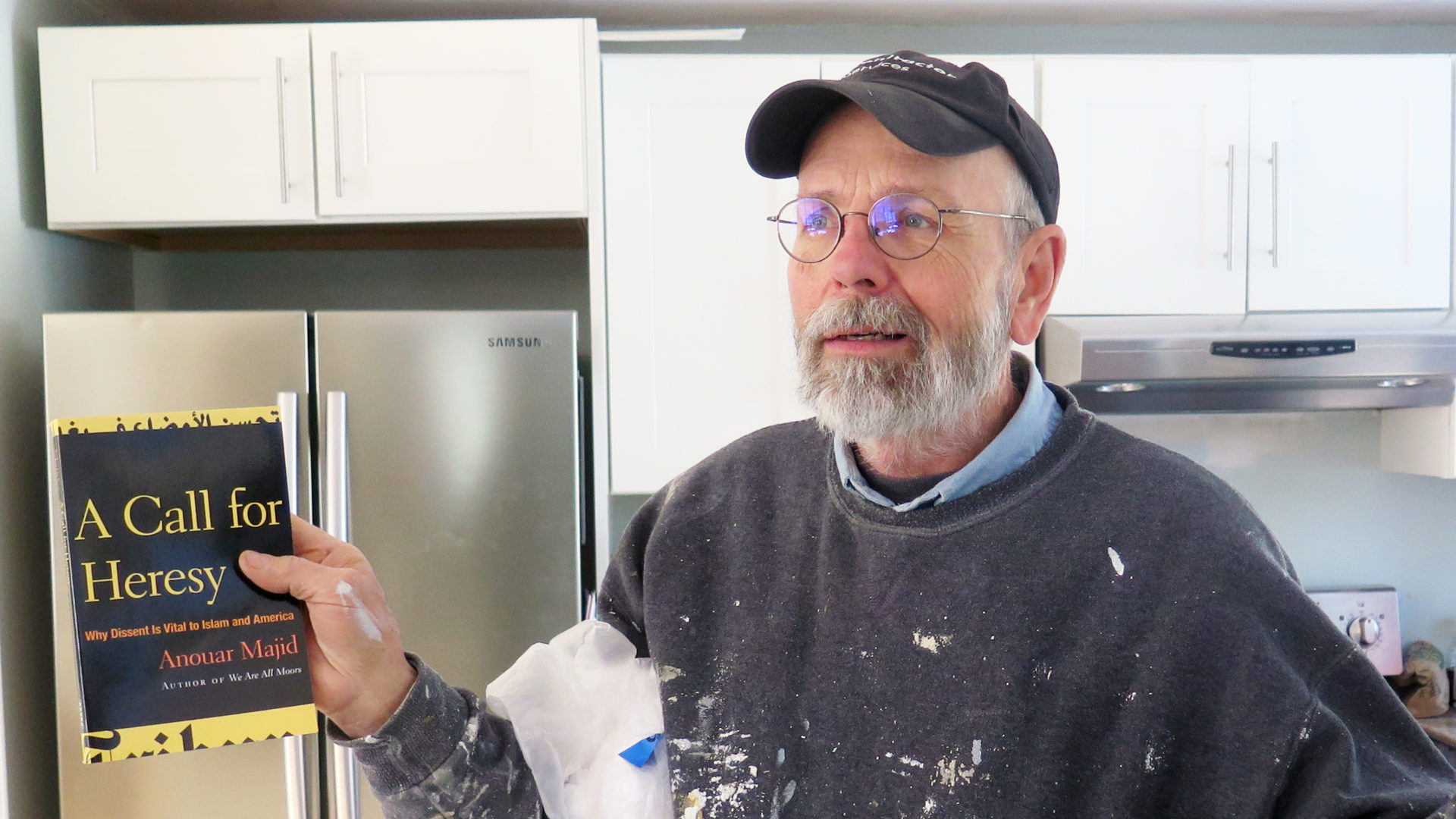

I wanted to share with him something and invited him to attend the University of New England’s Center for Global Humanities‘ lectures. But then I realized he lives in York County, too far to make the round trip to the city of Portland conveniently. I told him that he can watch the lectures live online; but, then again, how do I share the lecture link with him if he has no email? While pondering a solution to this conundrum, I offered one of my books, explaining that some are denser than others. “I prefer dense ones,” he replied unhesitatingly. Not knowing whether he would enjoy postmodern debates and such, I gave him A Call for Heresy. His face lit up, but he resigned to having to wait till his wife was done with it. “She would want to read it first,” he stated. I added a bottle of French wine and, in an attempt to connect with his Greek self, described myself as Epicurean. He smiled philosophically. I walked out to my car and drove in the striking February sunshine. When I returned home, I found out that he had screwed curtain rods into the shallow drywall in my daughter’s room. After a year of waiting, we could finally hang a curtain and darken the room.

Thank you for this excellent story!