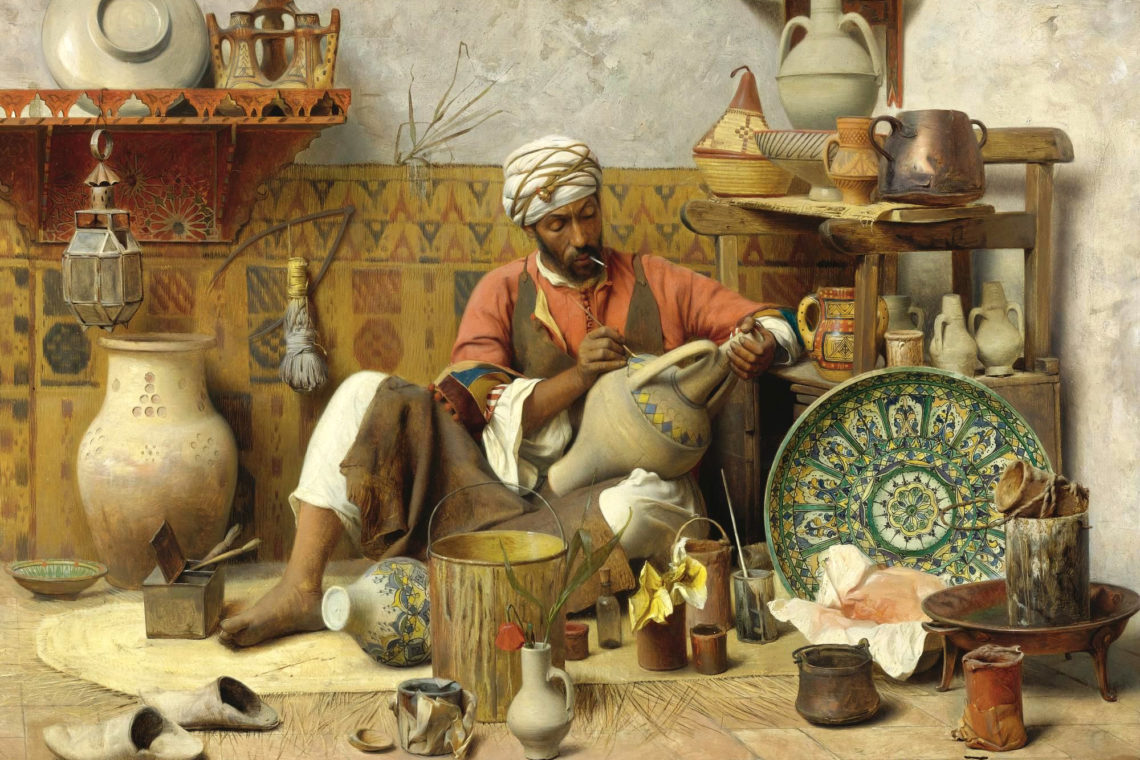

The title of this album, released in 2009 by ECM Records, means “balance” in the language of Aljamiado, which developed in medieval Andalus. Aljamiado was a hybrid language of Latin and Arabic derivation, which revealed the confluence of cultures in what we now call Andalucia in southern Spain. Siwan evokes the spirit of Al Andalus at the height and denouement of the Muslim Empire, a time of cultural mixing, when Jews, Muslims and Christians coexisted and produced scholarship and art together.

Composer Jon Balke explores balance not in terms of stasis, but of multiple voices working in cultural counterpoint. Balance is a momentary and elusive ideal. This musical process is unpredictable and, at its best, unearthly in its emotional power. We are invited into an imagined Andalusian world created by Balke, a virtuoso composer, arranger and pianist. He brings together the Gharnati tradition of classical Andalusian/Moroccan music and the baroque sound of Bjarte Eike’s Barokksolistene (Baroque Soloists), a Norwegian ensemble that performs early music of the European tradition. Balke is a brilliant collaborator, who has brought together Amina Alaoui (a Moroccan Gharnati singer), violinist Kheir Eddine M’Kachiche from Algeria, and other artists from different musical traditions to explore this new sound. He does this by creating a musical structure that supports the differing improvisations of his collaborators, much like jazz.

What brings together jazz, Baroque, and Gharnati music (as well as Arab and flamenco music in general)—and what is foreground in this fusion—is improvisation. This is known as taqasim in Arabic music, and familiar to the Western ear in blues and jazz. Less familiar to many is the role of improvisation in European Baroque music. Improvisation allows the individual musician/singer to create an original composition on the architecture of a melodic structure. In flamenco, Andalusian and Arab music, as well as in jazz, there is a call and response form to the improvisation. A singer may sing a verse and other instruments (or a dancer, in flamenco) will offer an improvised response to that verse. Improvisation is highly prized in these musical genes, which grew from small performing ensembles. Though Baroque music was the only written genre, skilled ornamentation was a crucial aspect of performance.

In addition, flamenco, jazz and Arabic singing have notes sung just below a Western half-tone. In Arab music, this is because of the quarter, eighth and sixteenth tones that are part of their tonal scales. In blues and jazz, these are known as “blue notes.” These similarities in style and structure bring Gharnati, Baroque, flamenco music and jazz into a common space for play.

Most of the eleven compositions on this album are set to poetry of the Andalusian period (roughly the eighth through fifteenth centuries) or to spiritual verse from shortly after. The songs are sung by Amina Alaoui in a Gharnati (Granada) style, which harks back to the late Andalusian period and is considered classical Andalusian music in Morocco and Algeria today. Sometimes the lyrics are in Arabic; sometimes, Spanish. Gharnati solo singing has the quality of water running smoothly over stones—one imagines the fountains and streams of the Alhambra in the gentle, light melisma of the voice. Alaoui doesn’t have quite this feel—she has more the huskiness of a flamenco singer—but this makes of her voice a hybrid sound, which brings a rich emotional depth to the songs.

There are many “soundscapes” created by Balke’s fusion and musical collaboration. For this reviewer, the most hauntingly beautiful are “Tuchia,” the first instrumental piece, and “O Andalusin,” based on a poem by Ibrahim Ibn Khafaja (1058-1139 AD).

In “Tuchia,” a base melodic line is played in unison (an Arabic style) in a Western musical scale, over which M’Kachiche’s violin improvises in an Arab maqam (scale). The interaction of these melodies create both dissonance and rich, unexpected resolutions, in a call and response structure. The piece ends in a final unresolved (in the Western sense) note—suspending us between the East and West.

“O Andalusin” is an elegy for the lost Andalus, a powerful expression of yearning for a beauty and peace that is no more. Rich baroque harmonies, with open chords, articulate a grandness into which Alaoui weaves her wistful melody.

Nothing is more beautiful, oh Andalusians,

Than your luxuriant orchards,

Your gardens, woods and rivers

And springs of crystal. . . .

Do not fear Hell

Or its dreadful sorrows

For none shall enter Hell

Who has found Paradise.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.