For the longest time, ever since my early childhood years, I have tried to imagine the lives of Adam and Eve, fashioned, unlike the luminous angels, out of clay. The Quran tells us that, for some reason, Allah decides to create Adam against the spirited objection of angels who correctly predict that he and his descendants would wreak havoc in the world. In the face of God’s insistence, the angels relent and accept this order of things, except for Satan (Iblis), who vows to corrupt and lead astray as many people as he can get to. To do so, he asks God to allow him to live as long as humans are around. God grants Satan’s wish and the cosmic drama was launched until the end of time. Instead of God punishing the insubordinate angel, he allows him to embark on his nefarious scheme. The only consolation of this dubious deal, I was told, is that God never denies anyone’s request, not even Satan’s, his implacable enemy.

I also learned that Adam and his partner Eve ate a fruit from a tree they were explicitly forbidden by God to touch and were, therefore, expelled from their paradisiac dwelling into an inhospitable world of endless toil and suffering. Adam and Eve, together or separetely, engendered children, including sons who kill each other, and out of this family of rebels and killers we came to be who we are. Still, the story has too many holes in it and simply gives up on trying to explain how the human race descended from this dysfunctional family.

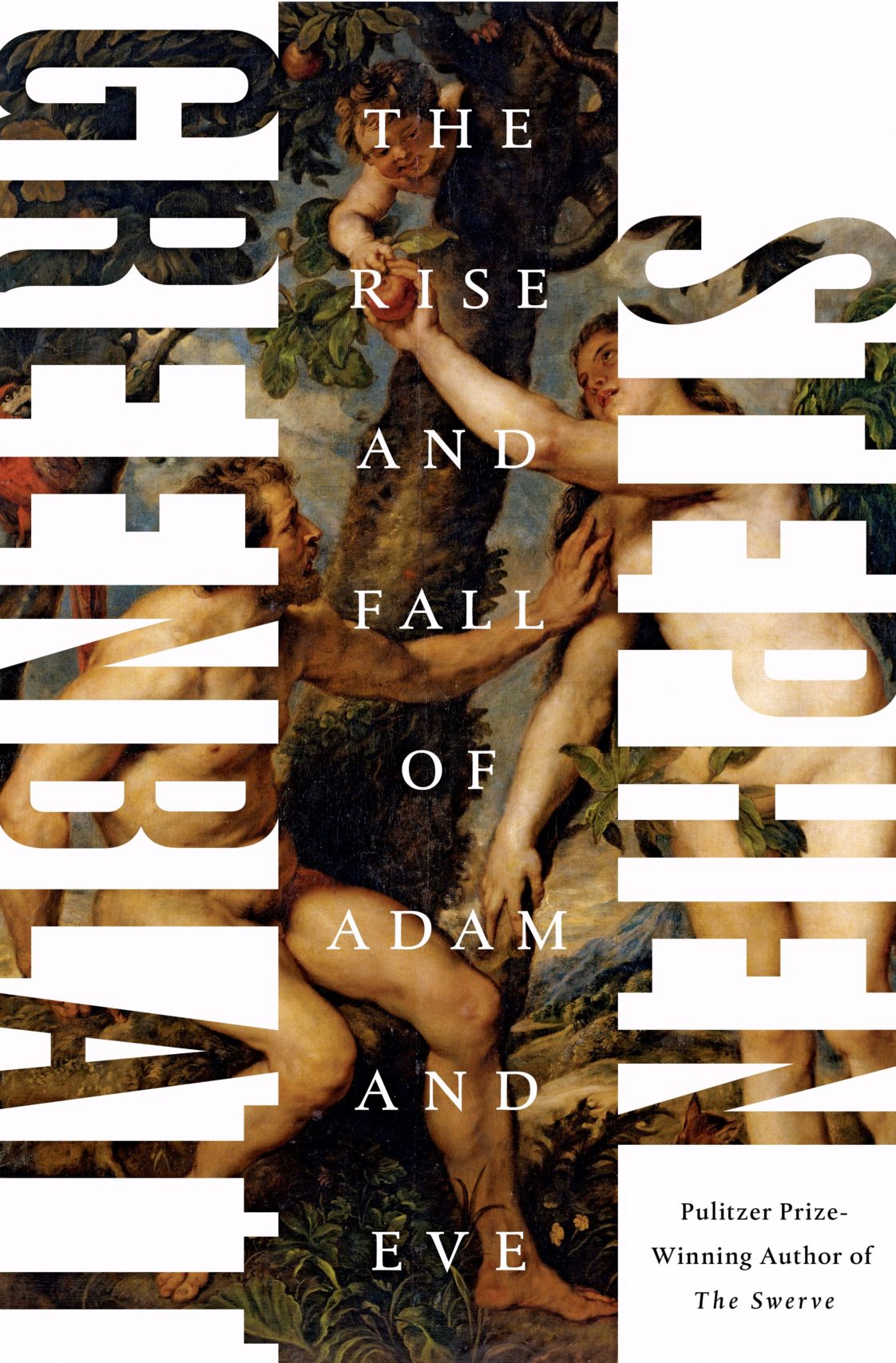

The story of Adam and Eve is only a page and a half long in Genesis, yet it has occupied people’s minds and shaped the way we think about ourselves and gender relations for millennia. As Stephen Greenblatt tells us in his new book, The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve, the Jews didn’t take the story seriously since, to them, it didn’t make much sense, while early Christian thinkers tried to read it allegorically. In one of the unorthodox gnostic gospels found in Egypt in 1945, even the serpent, accused of tempting Eve, is surprised that God doesn’t want his creatures to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. So nonsensical is the story that the Christian leader Marcion suggested doing away with the Hebrew Bible altogether. The Roman emperor Julian wondered what kind of language the serpent used to address Eve. (The serpent, in the emperor’s reading, is actually the savior, not destroyer, of the human race.)

The story of Adam and Eve would have been relegated to a minor tale had Augustine of Hippo, an Algerian bishop, not recast it as a foundational and fateful event. A remarkably gifted student and scholar, Augustine, under the relentless pressure of his fanatical mother Monica, came to regret his early sex life after he converted to Catholicism and set out to craft a new theory of humanity and Christianity out of the threadbare details of the story of Adam and Eve in Genesis. Reexamining his own personal life—involuntary arousals in the bathhouse with his father at age 16 and the “ardor of lust” (he called it “concupiscence ) with his mistress of 13 years—Augustine formed a theory (though he couldn’t find convincing literal evidence in Genesis, a project that consumed him for 15 years) of human sin as the ultimate sexually transmitted disease. In Augustine’s view, since lust erupts in our bodies and escapes our powers of control, it leads to all sorts of suffering and misery. Sex, therefore, is the originale peccatum (Original Sin), through which the human species became a “massa peccati, a lump of sin.” It is a genetic flaw from which Jesus was spared. It is, therefore, through Jesus that one can be liberated from the tyranny of concupiscence, even though a return to the (improbably) serene and dispassionate intercourse that must have preceded the era of lust can no longer be the lot of humans.

Augustine’s logic was disputed by the British-born monk Pelagius and by the Italian aristocrat Julian of Eclanum who considered such dark and damning views as the work of an Osama bin Laden type, “a set of weird, uncivilized beliefs concocted by a domineering psychologically twisted demagogue.”

But Augustine, undaunted, prevailed. As Greenblatt put it: “Through intellectual mastery, institutional cunning, and over-powering spiritual charisma, this one man managed slowly, slowly to steer the whole, vast enterprise of Western Christendom in the same direction. It is to him preeminently that our world owes the peculiarly central role that Adam and Eve came to occupy.”

Not only that, but “Augustine opened the floodgates to a current of misogyny that swirled for centuries around the figure of the first woman.” To be sure, blaming women is a trope that predates the story of Adam and Eve, going all the way back to the Greek myth of Pandora who opens a carefully sealed jar and lets out all the “ills that have afflicted humankind ever since.” Early Church fathers like Tertullian and Jerome, a contemporary of Augustine who translated the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate), blamed women and marriage but held a sacred place for Mary who atones for the sinful nature of her progenitor. (“Eva became Ave,” in this Christian reversal.) In the Middle Ages, the notion grew that Eve was fashioned out of Adam’s crooked or curved rib, that she cavorted with the devil, engaged in witchcraft through satanic powers, and probably was the real serpent.

Many centuries later, John Milton, unlike Augustine, self-consciously and deliberately clung on to a life of chastity, avoiding the pitfalls of college life and saving himself only for “married chastity” (sex within the bounds of marriage). Unlike men before or after him, he thought that virginity is not incumbent on women only, but even more so on men, since Adam is made in the image of God. Even a Grand Tour and spending more than a year in Italy would not sway him from his steadfast goal. He just would “not be seduced.” The rebellious poet eventually married many times, engendered children, got in trouble with the king, grew blind, and became relatively poor. But he was able to write what, in Greenblatt’s opinion, is “the greatest poem in the English language”: Paradise Lost.

The poem, with more than 10,000 lines, oddly enough, is an affirmation of humanity, defined by an act of irreversible transgression. Adam asks for a mate (the animals he names won’t do for companions) becasue, in the end, who wants to be in paradise alone? “In solitude/What happiness?” Adams complains. Consequently, Eve is extracted out of his ribs. Allowed to roam free, she chooses to fall by plucking the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and eating it. After some deliberation, she shares it with Adam who, knowing full well the consequences of his actions, chooses to eat it anyway. Immediately, the couple’s Edenic relationship is reduced to a human marital drama, leading Adam to chastise his partner and loathe all women. But Eve apologizes and Adam relents. The two kneel down to ask God for forgiveness, but God, unlike Adam, doesn’t relent. After the archangel Michael shows Adam what to expect in the world, the couple is expelled from Eden.

The French Isaac La Peyrère, a Protestant with Portuguese Marrano origins and a contemporary of Milton, found the story of Adam and Eve in Genesis nonsensical. In light of the discovery of America, La Peyrère had a hard time believing that native Americans were descendants of the survivors from Noah’s Ark. So, in 1655, with the help of Danish collector of “curiosities” named Ole Worm, he published a book in Amsterdam titled Prae-Adamitae, later translated in English as Men Before Adam. The argument was simple enough: Adam and Noah are Jewish stories, not for people in all places and all times. The world was peopled when Adam made his appearance. The reason people were confused is because the Bible is badly written. This was enough for La Peyrère’s book to be burned and him to be charged with heresy. He was arrested and forced to recant his views, which he did under duress, and spent the rest of his life in obscurity.

In 1697, the French philosopher Pierre Bayle, a Protestant by faith, published A Historical and Critical Dictionary in Amsterdam, a book about all kinds of subjects and stories that eventually grew into “6 million words in length.” One of the topics he discusses is the story of Adam and Eve. After asserting the main lines of the story, he raises a host of questions that have the effect of turning the biblical passage into a ridiculous tale.

Much like La Peyrère, Bayle suffered real consequences for his daring mind, but, at least, he died in his bed in Rotterdam at age 59. His cause would be taken up by Voltaire, author of the Philosophical Dictionary, first published in 1764. The man who urged his friends to “crush the infamous thing” (“Écrasez l’infâme”) in his letters, resorted to “outright mockery.” He blamed St. Augustine, whose notion of Original Sin, Voltaire wrote, is “a notion worthy of the warm and romantic brain of an African debauchee and penitent, Manichaean and Christian, tolerant and persecuting—who passed his life in perpetual self-contradiction.” Not unsurprisingly, Thomas Jefferson admired both Bayle and Voltaire, owned their books, and had the latter’s bust in his Monticello residence.

The story of Adam and Eve had no chance as scientific knowledge continued its resolute march. In The Descent of Man, published in 1859, Charles Darwin never mentions the fateful biblical couple because in his theory there is simply no paradise, only an earth that is tens of millions of years old. But Darwin’s earthshaking conclusion, based on scientific evidence, robbed him of the pleasures of literature and art. Although it is scientifically impossible to prove, the tragedy of Adam and Eve, as demonstrated over millennia, is a parable about human life itself: our struggles, dilemmas, pleasures, hopes and fears. It is a myth, as Greenblatt readily admits, but it has the power of literature. That is why it has endured.

There are many other fascinating stories in Greenblatt’s book, but what stands out to me is the author’s lyrical humanism and his mesmerizing skills of storytelling. The book doesn’t have the intensity of The Swerve, Greenblatt’s suspenseful story of how a poem from the first century, On the Nature of Things, was rediscovered by the book hunter Possio Bracciolini in 1417 and ushered in the modern world. But The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve is equally gripping, if only because it reminds us why religions can never be taken at face value and why we need talented humanists to show us how an unflinching passion for a life of letters can set us free.

Comments are moderated by the editor and may not appear on this discussion until they have been reviewed and deemed appropriate for posting. All information collected is handled in a manner consistent with our privacy policy.